Recent misunderstandings circulating on Weibo about admission to Cambridge University have shone a spotlight on the controversies surrounding the increasing numbers of Chinese youngsters studying in the US and the UK.

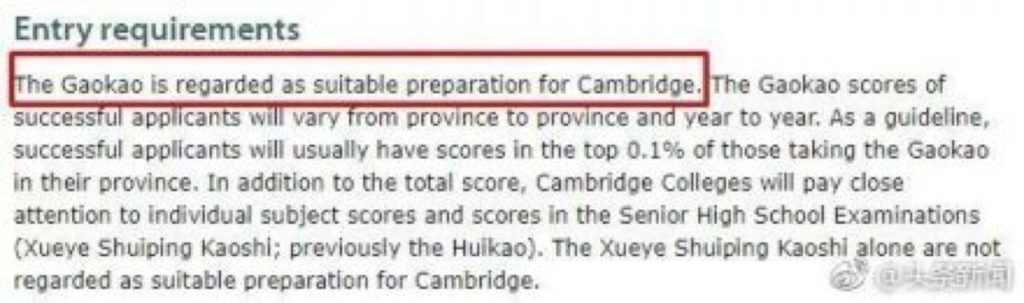

China’s equivalent of Twitter buzzed around an image being circulated from Cambridge University’s website, about their admission procedure. The (genuine) screenshot announced that Cambridge would accept the Gaokao (China’s university entrance test) as a qualification. Less pleasing was the suggestion that applicants would need to score in the top 0.1 percent in their province.

The screenshot circulating on Weibo

Despite this, netizens rejoiced that they could apply for Cambridge with the Gaokao alone, without the need to take the IELTS test demonstrating their English language capability. There’s only one problem: this isn’t true.

Cambridge has been accepting the Gaokao for many years; the Chinese test is recognized as one of the most academically rigorous in the world. However, applicants also need to score 6.0 or above on IELTS (or an equivalent test), with no less than 5.5 in each element. Even if Cambridge decided unilaterally to relax this criterion, it’s a legal requirement for a UK student visa.

Furthermore, Cambridge also assesses applicants on their wider interests and aptitudes, looking for students who have rounded personalities, possess skills of critical thinking, and will enhance the overall life of their college, whether through sports, arts, or other secondary activities. This is going to be a more challenging requirement for anyone who has spent years in the sort of intense tutoring many see as giving the best chance in the Gaokao.

It’s not clear how the misunderstanding arose. China Daily suggests that it was triggered by a speech given in Beijing recently by Stephan Toope, Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University. However, the idea that students, however academically brilliant, might be admitted to one of the world’s top universities without having to demonstrate aptitude in the language used for teaching, highlights differences in perception of the purpose and value of degree-level studies.

The recent scandal about children of the rich “buying” their way into top universities illustrated the trend in recent years to the marketization of universities. Professors complain that these students are eating up faculty time and dragging down standards for everybody; but they do so anonymously, fearing reprisals from administrators for whom these students represent a valuable source of income.

And the same is true of international students, and particularly Chinese students. “In my experience,” writes Adele Barker, a professor at Arizona University, “most of these students arrive here with not enough English to succeed and scarcely enough to pass, if they do at all. Last year, all 20 of the Chinese students who took my 100-level Russian history course failed. Why? They couldn’t understand my lectures. They were unable to read or write in English… And yet without enough English to succeed, or in most cases even to pass, the Chinese students keep arriving on campus. What is going on here?”

Professor Barker is concerned that the students are not receiving the education for which they are paying so heavily. She suggests that the problem is due to the “Faustian bargain” between students and universities: “The Chinese students need us for the elite status, the high-paying jobs and the lifestyle they so desperately want back home. We need them to help us keep financially afloat.”

The problem is still more acute for British universities, which, in a single generation, have seen the end of student maintenance grants, a huge expansion caused by the reclassification of vocational “polytechnics” as universities, and the introduction of tuition fees. Instead of students competing for places, universities are now competing for students, and the temptation to lower standards is immense.

I can offer some personal experience of this: in my brief time teaching Creative Writing at a UK university, I had one Chinese student who attended no lectures and whom I never met in person. She emailed me with a sample of poetry, asking if it was likely to be good enough to pass. I responded saying that it was impossible to prejudge her final result, but that the sample was quite good, and I offered her some advice on writing poetry. Her final submission though was a short story in a completely different style. The university authorities, clearly already suspicious, invited her to a meeting to discuss her story and produce some further writing in person. She neither responded nor attended the meeting, and was subsequently expelled on the basis that she was buying her work online.

This is, of course, a single piece of anecdotal evidence, but what was striking to me was that it was neither a scandal nor a shock, but a smooth and well-established procedure, in response to what appeared to be a common problem.

Chinese broadcaster CCTV recently suggested that Brexit might offer more opportunities for Chinese students as UK universities lose links with their European counterparts. It certainly seems likely that the UK will be offering student visas as a bargaining chip in trade talks with countries like India. However, this perhaps underestimates the extent to which the Brexit vote was driven by anti-immigration sentiment.

What is certain is that if western universities fall into the trap of lowering standards to secure more lucrative overseas students, then ultimately their appeal to those students will wane; they run the risk, through avarice, of killing the goose that lays the golden egg.

Photos: Diliff via Wikimedia Commons, screenshot from www.weibo.com