Our visit to Caochangdi art district is spontaneous and unplanned. We had been at a laser tag party at StarTrooper, which is nearby, and I noticed the signs as we passed.

“We may never come here again,” I say. “Let’s go and have a look.”

The response from the boys is unenthusiastic, though less vehement than their reaction to visiting 798. They are both crashing down from an adrenaline and sugar high, and I take advantage of their lethargy to spring some culture on them before they can muster any objections.

And Caochangdi is a quieter, calmer place than the frenetic 798; almost like a Mediterranean village on a sleepy Sunday afternoon, a tangle of streets and alleys, draped with bundles of overhead wires. No two buildings are alike, and round every corner you can find tiny boutiques and oddities like obsolete vending machines.

It’s easy to see why it would have appealed to artists such as Ai Weiwei, who moved there in 1999. In his wake came a wave of studios and galleries in what remains an otherwise resolutely ungentrified corner of Beijing.

The first of these we encounter is the Amy Li Gallery, with its eerily undulating brick walls. Peng Jian’s Facing the Light seems facile at first, paintings of piles of books and Rubik’s cubes, until we begin to notice the games with perspective, almost Escher-like at times. Lines diverge which ought to converge. Are those things set back from each other, or floating mysteriously in mid-air? Is that a cluttered study, or a cityscape? Is that a shadow, or –

“Why do you keep asking questions?” Joseph interrupts.

Because that’s what art is meant to do; to make you question things.

“Oh,” he says.

Noah is more taken with Sun Hao‘s ink paintings of horses, though some of them are too literal for my tastes. Bai Ye at Telescope is anything but literal, and I peer at the framed images trying to work out what they are: heavily processed photographs? There is a plaster landscape, an assemblage of black plastic shapes on a table. In the small space of the studio the effect is disorienting, almost dizzying.

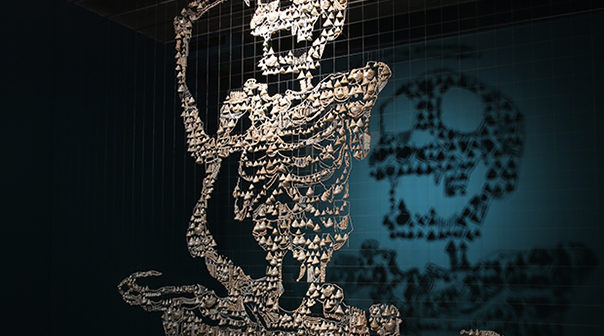

At Chambers Fine Art though we are unanimously awestruck. Our first encounter with Wu Jian’an’s Ten Thousand Things is Shallow Mountain, 1,500 old bricks, each uniquely carved and etched, lined up in ranks like an abstract Terracotta Army. Noah enters the next room before me and I see his jaw literally drop. Big Skeleton is an enormous monkey skeleton constructed from sea shells. Closer inspection reveals that many of the shells are delicately painted in a traditional Chinese style.

The other works in the exhibition, while less staggering, are all intriguing: dinosaurs made from snake skeletons and deer antlers, enormous collages of intricately cut paper figures. 500 Brushstrokes appears to be a normal abstract, but in fact each brushstroke has been cut out and reassembled on a new canvas.

As we stumble into the light Joseph is eager to get home and start making art himself, but we are now in the brick maze at the heart of Caochangdi, and major galleries are right in front of us. Li Jin’s ink paintings develop a traditional Chinese technique for the modern age, and reveal his obsessions with food, Buddhism – and the female body, more conservative parents may wish to be warned. My kids, usually so keen to snigger at nudity in art, don’t even notice though, being fascinated by a video of Li Jin at work, revealing his mastery of the brush.

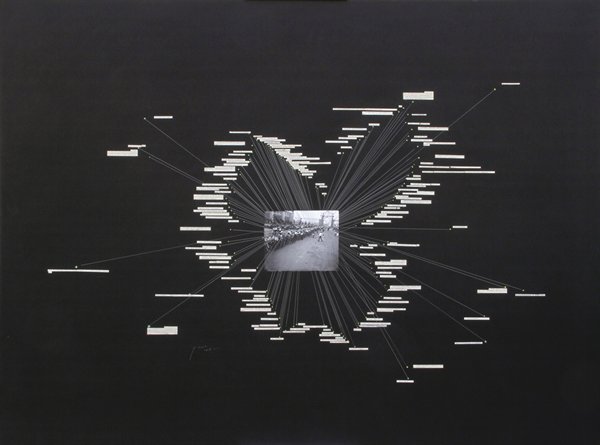

Yao Peng’s Ladies and Gentlemen consists of old black and white photographs of crowd scenes, with lines drawn from each individual to a tiny printed strip of paper on which their hidden thoughts are revealed. Noah has fun trying to decipher the Chinese, but Joseph is wearying, so we head for home.

On the way back to the main road we notice a row of caged birds, with wild sparrows clustering on the telephone wires above them. The boys speculate on what the birds might be saying to each other, comment on the difference between the neat lines of cages and the chaotic crew above them. The art at Caochangdi has done its job, I think: however tired we may be, we are all a little more alert to the world around us.

Photos: Chambers Fine Art, Andrew Killeen, Beijing Art Now