At three-months-old, Marianne is already becoming garrulous. For weeks, she’s been getting well-versed in the art of baby babbling (which is a bit early– most babies start at about four months). Crying, of course, remains her primary mode of expression, but over the past few weeks she’s been throwing a lot more “woooaaaaaa”-s and “haiiiiiii”-s into the mix. Watching and listening to her try to verbally communicate with us is as fascinating as it is cute; and as our baby becomes progressively more alert, I like to envision how quickly her brain, with its infinitesimal network of neurons and synapses, is developing.

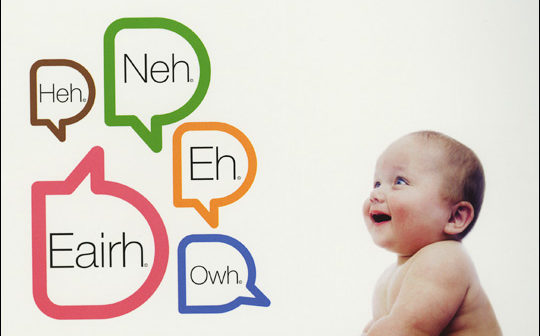

Even more interesting is the notion that many of the sounds she’s been making since birth can be decoded into actual meanings, according to Dunstan Baby Language. . Wikipedia describes Dunstan Baby Language as a “claim” that babies across cultures can express themselves through a series of similar sounds: “neh” for “I’m hungry,” “ow” for “I’m sleepy,” “heh” for “I’m uncomfortable,” “eairh” for “my tummy is bloated,” and “eh” for “burp me!”

This language theory is not without its criticisms – primarily that it cannot be qualified as a scientific theory due to a lack of quantifiable methodology and empirical research, not to mention the very commercial nature of its online presence. But interacting with Marianne has me quite convinced that there is at least a kernel of truth to the idea. Since day one she has indeed made those five sounds on a frequent basis (at first, pretty much exclusively), and two of the sounds in particular (“heh” – for “I’m uncomfortable,” and “eaaaaaaairhhhhhh!” – “my tummy is bloated”) are usually quite pronounced and clearly correspond to their prescribed meanings (the former she usually makes if we hold her aloft for too long periods of time – she’ll typically pant out a string of “heh-heh-heh”-s when her neck gets tired – and the latter she wails out when she’s having a bout of colic at nights).

I can also understand why the scientific community seems to balk at the idea given the lack of hard data to back up Dunstan’s claims, but it makes sense to me that human babies, like all infant animals, use similar audio cues to signal basic needs to their parents. In any case, judging from the spring-to-action-by-jumping-out-of-bed response my wife makes when she hears Marianne’s cries in the middle of the night, they work.