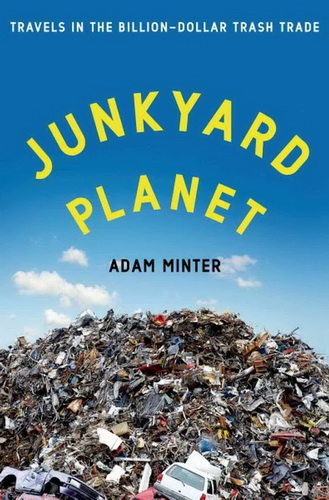

For the second week of the Bookworm Literary Festival, both Myles and Brigid excitedly asked each morning, "Is this the day we see Adam? When are we going to see Adam?" I think the thrill of actually knowing an author beforehand was a pretty big deal to them. By that Wednesday I could assure them that yes, that was the day we would see Adam, as we would again the following evening. Both events were part of his promotion of Junkyard Planet, which I really enjoyed on its own merits, knowing the author or not. And a big bonus was that I finally was going to meet Adam’s new wife, Christine. She in turn presented me with my very own Junkyard Planet swag.

On Wednesday we saw Adam talk about the global scrap trade on a panel with several other journalists and activists. Then on Thursday night he talked about his book with Sinica podcast host Jeremy Goldkorn.

When I bought the tickets for "Future Perfect: Sustainable China," the event was advertised as a panel of two. That number grew, though, to include not only Adam and John Kaiman of the Guardian, but also several other people whose names I did not write down because I thought I would find them elsewhere online. I did not. But there representatives from the Nature Conservancy, Greenpeace China, and the online editor for the Chinese-language New York Times. It was a good panel, with Adam in the expanded cast playing a bit of an outlier role. The other four were either activists or journalists, looking more at the effects-end solutions to environmental problems (consumer recycling, air quality, and water quality the subjects they most talked about) in contrast to Adam’s background and his book about how development demands recycling. The discussion and Q&A mostly focused on what consumers can do to prevent further environmental damage, like not buying a particular product or demanding more responsibility from consumer brands. The editor from the New York Times had one interesting point of view for the situation in China; she said that as long as people keep emigrating from China because of the pollution, the government will eventually have to do something.

Through the panel discussion, I wondered about how much consumer choices made in China impact the environment. Recently hard data was published concerning how much manufacturing for export has affected the environment in China. Further, many of the sources of pollution are in sectors that are removed from consumer choice on any continent. The chart found at this link shows a breakdown of targeted industries for reporting and (hopefully) clean-up. These might not be contributors to air pollution in the same ratios, by the way, but with heating, electricity generation, steel, and cement receiving the bulk of the scrutiny, consumer pressure won’t carry a lot of weight. Finally, I have to wonder how China would balance shuttering some of these industries with any unemployment that would result.

During the panel, Brigid drew a pretty good likeness of Adam.

The following evening, Jeremy Goldkorn interviewed Adam at the Literary Festival for the the Sinica podcast. This hour was focused on Junkyard Planet and the kind of things that come up in the book that are unknown or overlooked in the usual reporting on scrap and recycling (again, it isn’t necessarily consumer-driven).

I was grateful Goldkorn and Adam delved into some of the background of the book. When I blogged about reading Junkyard Planet, I noted how much I appreciated Adam revealing some personal details about his family background and specifically anecdotes about his grandmother. In the book, too, there are also some unfortunate parts about his father and substance problems he had faced leading to financial decline, all of which I wasn’t even comfortable discussing here. Goldkorn asked Adam directly about why he elected to incorporate these aspects of his life into a book about scrap. Adam opened up further than he did in his book, explaining that he felt it was important to show how, even with all this intimate knowledge of the scrap trade, there are reasons why his family members aren’t millionaires. Further, he and his wife had discussed what other non-fiction books they had found to be compelling reads, and many of them included a personal angle. It was decided, then, to put it all in there.

Another great question Jeremy posed was about the code-words that scrap dealers use to describe a given mix of material. For instance, scrap traders throw around words like "honey," "barley," and "ocean," when they are involved in a transaction actually dealing with copper or brass. Adam explained there (and also in his book), that these are material designators, the origins of which date back to the early twentieth century. During that early boom of the scrap trade in the US, scrap peddlers and reprocessors needed to come up with a standard system to communicate what was in a given bundle of scrap. Back then, one of the biggest needs for recycled material was the paper industry, and the mills would pay different prices for a load of clean white cotton, or soiled white cotton, or black stockings. As the standards were developed and expanded to include metal products, four-to-six letter words were used as designators were attached to each grade of scrap since many of the transactions took place over the Teletype. The word "lake" was a lot less expensive to transmit than the more complete description "brass arms and rifle shells, clean fired." The system of short words standing in as material designations has remained to this day even though the industry no longer relies on the Teletype. This is more than just interesting minutiae; it goes to show how formal and organized the scrap industry is, and has been for nearly a century.

One of the more amusing parts of the book (and the chat between Goldkorn and Adam) is that Adam’s wife Christine, on seeing an automobile shredder for the first time, referred to it as the sexiest piece of machinery she had ever seen. She has a point; they are massive, earth-shaking, three-story monsters that can chew up one hundred thirty tons of cars in an hour. I leaned in to her when this came up, and joked that she thought this because she hadn’t seen an eddy current separator in action yet (VPN needed). An eddy current separator , by the way, is a piece of equipment that passes scrap over moving permanent magnets, inducing eddy currents in the non-ferrous metals (like aluminum cans or even hunks of aluminum slag), causing them to fly off the belt to some distance away. It’s a pretty cool system. Randy (yes! even Randy was there! at the Bookworm!) heard my whispering, and after the program was over, handed his phone to Christine. He showed her one of a number of videos he carries around with him that shows one of his customers’ eddy current separation systems. It was as if to prove we were kindred spirits in dorkiness.

The final Q&A again veered more towards consumer participation in scrap and recycling. In the course of some of his answers, Adam took precise aim a certain electronics brands. I feel as though one of the main points (or one of the main things I took away) from Adam’s book got muddied at this point. The global scrap and recycling industry did not achieve its size and status primarily out of anyone’s noble sense of environmental responsibility. It was because materials were needed, and reprocessing was cheaper and/or more readily available than virgin product. If consumer electronics aren’t right now recycling-friendly, it is because the materials that go into them are still reasonably priced and available. When developing countries needed aluminum, copper and steel, the eddy current separator and automobile shredder came into existence. The burden wasn’t on the automotive manufacturers to facilitate cars’ afterlife. Of course, the consumer climate these days is that we often demand some sort of responsibility from brands. But I don’t know if today’s obstacles to recycling of certain devices are permanent. At some point, some material that is used in abundance in our mobile phones and tablets will become scarce or expensive, and the enterprising and desperate will find a way to mine the scrap that is out there. In my own sphere of experience, rare earth magnets, there are many reasons why recycling product is not simple. However, for Mitsubishi’s air conditioning division, there was plenty of motivation to design for recycling magnets. They are able to reclaim the magnets in their own scrapped A/C units, but only from their own. Pricing and availability of NdFeB magnets in the past few years prompted this development, not necessarily their or their customers’ concern for environmental conditions at rare earth mines and magnet manufacturers. I’m all for consumers wanting more from the companies to whom we hand our cash, but I understand why certain demands might be difficult to be satisfied today.

Both events were not only great opportunities to see one of my oldest friends in China, but also to enjoy hearing him talk about a subject that, as the pin Christine gave me said, I didn’t know nearly enough about before I knew him.

This post first appeared on Jennifer Ambrose’s site on March 29, 2014.

Jennifer Ambrose hails from Western Pennsylvania and misses it terribly. She still maintains an intense devotion to the Pittsburgh Steelers. She has lived in China since 2006 and is currently an at-home mother. With her husband Randy and children Myles and Brigid, she resides outside the Sixth Ring Road in Changping, northwest of Beijing

Photos courtesy of npr.org and Jennifer Ambrose