I do try to attend some of the programs for adults at the Literary Festival. Some years I am more successful than others.

This year I had high hopes; I even bought a few books on the pre-Festival display that looked very interesting (like Radhika Jha’s Smell, Michael Meyer’s In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China, and Tim Cope’s On the Trail of Genghis Khan), but when the schedule was released, the timing for their events didn’t work for me. There were other talks, too, I would have liked to attend, but, again, I couldn’t make them.

There is one recurring event, the annual panel of foreign correspondents, that I have always wished I could see, but often it sells out before I even get in line. I would also feel guilty about buying up seats for my kids that would otherwise be occupied by much more engaged adults. So I usually pass on even considering it as an option when I am mapping out our Lit Fest schedule.

This year, though, after the Festival had started and the tickets had been on sale for a few weeks, I learned that "Committing Journalism" still had many tickets available. It would be the next week, in the afternoon on a day we were already planning on being at the Bookworm. I could not pass it up, especially since the rest of Beijing had their chance to buy tickets already.

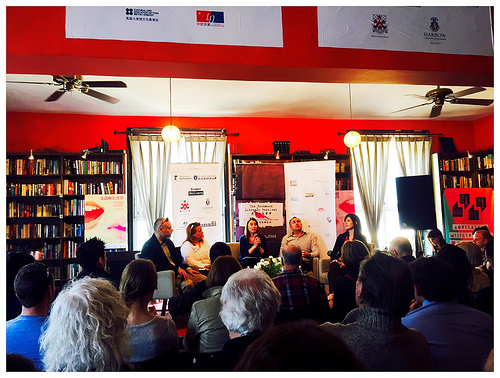

The moderator for "Committing Journalism" was Louise Watt of the Associated Press. All four of the originally scheduled panelists were also there: Anthony Kuhn of NPR, Laura Daverio of RSI, Andrew Jacobs of The New York Times, and Laurie Burkitt of The Wall Street Journal.

I had told the kids that they could plug in their headsets and watch something silently on their iThinigies, but I at least wanted them to listen for a few minutes to see if they were actually interested. Brigid was quick to plug in. Myles was about to himself, until he heard and recognized Anthony Kuhn’s voice.

"He’s on ‘All Things Considered!’" he whispered to me. After that he was attentive.

I was surprised to hear that Kuhn was feeling, in general, optimistic about the reporting environment in China. In the recent years the international press in China was shocked with multiple visa-denials, even of long-time correspondents. However, Kuhn remained hopeful about conditions. His perspective was a very long view—he was first reporting from China in 1982, so he recalled a much more restrictive environment that even dictated precise locations journalists could live, something that had been lifted in 2004. He was also recently reporting from Myanmar, where in a relatively short period of time he had witnessed a lot of change toward openness.

One of the things that Myles really picked up on from Kuhn was his mentioning that there were times, especially during his earlier reporting days, when he had to explain to people that foreign correspondents from the US were not government employees. The "National" in "National Public Radio" was misleading to people for whom "National" always translated as government entity. Myles was very amused that Kuhn had even received mail to his office that was addressed to the President. Myles still talks about that.

The others in the panel also outlined some of their obstacles to effective reporting. For someone like Burkitt, who usually focuses on business stories, the opacity of financial data, even with publicly traded companies, is a problem. Daverio sometimes struggles with sources who don’t want to speak on camera; the video often makes its way to the Chinese Internet.

Towards the end, two of the American journalists voiced concern about their fellow correspondents’ ability to secure visas and credentials. Jacobs himself noted that if he were to leave China, The New York Times may not be permitted to replace him in the Beijing office. While this is certainly troubling for the news organizations, the problem is, as Burkitt said, that the American press needs the Chinese government a lot more than the government needs the foreign press. There was some discussion of lobbying efforts, too, in Washington, to bring this matter to the attention of the State Department, perhaps to get some diplomatic leaning to keep the American press in business. The question I wanted to ask, though I was too shy to try, was that if this were the wisest course of action for the news organizations as it flies in the face of appearing as free and independent of the US government.

Kuhn’s final concern was definitely interesting, too, and it spoke more to the struggles within an international news organization itself. Not just at NPR, but much of the US press have developed a model where a lot of the reporting decisions are made by editors in places like Washington or New York. For instance, his editors were directing him to follow up on stories that were everywhere (ad nauseam, I might add) the week of the event: the purported ban on dancing grannies, the use of gutter oil in planes, and a micro-trend of strippers hired for funeral parties. Kuhn dismissed these with amusing, snappy one-liners (on gutter oil in planes: better there than on my dumplings; on funeral strippers: well, that’s one way to go out). I appreciate what Kuhn was getting at—that there are certainly stronger, more important stories out there that receive less attention while everyone else is talking about these other things. I love a good, amusing, human interest piece, like the reporting that in NPR parlance is called "Driveway Moments." But unless there’s a new angle to something I’ve heard or read already, there’s no Driveway Moment.

At the very end, during the Q&A, Willis Barnstone stood up to comment on his perspective on conditions in China for foreign writers. I was rather gobsmacked to realize he was sitting only two rows ahead of me all that time, and that he stood to speak, that I forgot to record much of what he said. His China experiences stretch back very far, to the 1970s. When I came to my senses, I did write down a very interesting tidbit that spoke to how the political climate can swing like a pendulum in China. Barnstone had translated Chairman Mao’s poetry into English, which was one of the reasons he had been welcomed to Beijing so early for an American. However, when he was to return to China in the 1980s on a Fulbright, his visa was delayed a year because the Chinese government was afraid he would be too sympathetic to Mao.

I understand why "Committing Journalism" is among the most popular of the Literary Festival. There’s something very interesting about the mechanics of reporting and writing, especially given the circumstances of China. After all these years, I am glad I finally got the chance to attend.

This post first appeared on Jennifer Ambrose’s site on April 14, 2015.

Jennifer Ambrose hails from Western Pennsylvania and misses it terribly. She still maintains an intense devotion to the Pittsburgh Steelers. She has lived in China since 2006 and is currently an at-home mother. With her husband Randy and children Myles and Brigid, she resides outside the Sixth Ring Road in Changping, northwest of Beijing.

Photos: Jennifer Ambrose