Last Friday was a perfect spring day in Beijing, so I couldn’t help but shirk work for a few hours to cross another item off my bucket list: Prince Gong Mansion, an imperial residence constructed by the most famous corrupt official in Chinese history.

Dodging tour buses and throngs of Chinese visitors, I cycled along Xi’anmen Dajie and turned north on Sanzuoqiao Hutong, a street I remembered well from the Ghost Tour I went on with Newman Tours three years ago. The entrance to Prince Gong Mansion can be found at the end of Sanzuoqiao, after a slight left.

I heard the crowds before I saw them: a sea of Chinese dialects swirling with the blare of megaphones and restaurants hawking zhajiang noodles. Upon entering the Prince Gong Mansion compound, it took me a minute to spot the ticket window; it was in the corner near the westernmost wall. Thankfully, there were separate admission lines for tour groups and individuals.

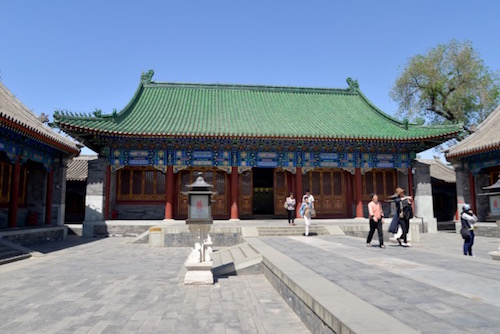

Prince Gong Mansion is divided into two parts: the residences and the garden. The six main residential halls are arranged roughly like a grid and separated from the garden by the largest building in the compound: the two-story, 160m-long Houzhao Lou (后罩楼).

The mansions were originally constructed in 1777 for Heshen, a court official in the employ of the Qianlong Emperor. He rose swiftly through the ranks, further cementing his position with the marriage of his son and one of the emperor’s daughters in 1790.

Heshen’s hold on power provided him with unparalleled freedom, and soon he engaged in open corruption. His misdeeds included nepotism, embezzling taxes, extending military campaigns to steal public funds, and doing away with official posts.

Heshen got his comeuppance in 1799, when the Jiaqing Emperor – the successor to the Qianlong Emperor – had him executed for corruption. The mansion was given to Prince Qing, the youngest son of the Qianlong Emperor. Fifty-two years later, the Xianfeng Emperor gave the residence to his brother, Prince Gong, whom it is now named after.

Before the site became protected in the 1980s, it was converted into a Catholic university by the Benedictines in the 1920s and used as an air conditioning factory during the Cultural Revolution.

Since 2005, RMB 200 million has been poured into renovating the buildings and gardens. In 2008, the site reopened to the public in its current form during the Beijing Summer Olympics.

Though I had a rough itinerary worked out for the visit, I ended up improvising because of all the tour groups. April 1 marked the beginning of the busy season, so I’d recommend visiting on a weekday morning before it gets too packed; weekends are out of the question, especially if you have young children.

The residential buildings were well-maintained but a bit sterile; I much preferred the gardens. However, some people might be interested in the exhibition on the history of Prince Gong Mansion and the Qing Dynasty; another hall contained contemporary Chinese art depicting the performing arts.

The main entrance to the gardens is through a stone archway called Xiyang Gate. Before going through, look back towards Houzhao Lou; it reportedly has 88 windows divided evenly between the first and second floors. Notice that the 44 windows on the second floor are all different from each other – a rarity in imperial architecture.

One of the first features you’ll see is Bat Pond, which is said to be in the shape of a bat. I don’t see it, but I suspect this is classic overreaching since the Chinese character for “bat” (fu) is a homonym for good fortune.

Slightly off to the right, there’s a charming little peony garden past a bamboo grove. Though most of the flowers were already starting to wilt, a few peony bushes were still in full bloom. I waited my turn as one young woman spent five whole minutes maneuvering a particularly lush blossom into place for a selfie.

Just past the peony garden is Miyun Cave, which contains a famous 8m-tall stele bearing an inscription of the character 福 (fu) by the Kangxi Emperor. I opted not to see it because the queue looked like this:

Instead, I walked up to the pavilion perched over the cave, accessible through two walkways located on either side of the hill. The view wasn’t anything spectacular, but I felt pretty smug looking down at the winding lines.

Strolling around the lake on the western side of the gardens was my favorite part of the visit. There were plenty of shaded areas to sit in, including the pavilion in the middle of the lake. It was an ideal place to relax and people watch.

In total, I’d recommend setting aside two to three hours for Prince Gong Mansion. For those who prefer a more structured visit, I found this great itinerary on Baidu Images. It hits all the main residential buildings, through the gardens, and around the lake.

I didn’t use them, but there were public restrooms scattered throughout the compound. Snacks and cold drinks are available onsite at slightly marked up prices. Generally, Prince Gong Mansion is stroller-friendly but requires going up and down the occasional steps or lifting the stroller over a threshold. Be sure to use sun protection, wear walking shoes, and bring plenty of water.

Prince Gong Mansion 恭王府

RMB 40 (admission only), RMB 70 (admission with Chinese-speaking tour guide), free for kids under 1.2m. Daily 8am-6.30pm (Apr 1-Oct 31), tickets sold until 5pm. 17 Qianhai Xijie, Shichahai, Xicheng District (8328 8149) 西城区什刹海前海西街17号

Sijia Chen is a contributing editor at beijingkids and a freelance writer specializing in parenting, education, travel, environment, and culture. Her work has appeared in Travel + Leisure, The Independent, Midnight Poutine, Rover Arts, and more. Follow her on Twitter at @sijiawrites or email her at sijiachen@beijing-kids.com.

Photos: Sijia Chen