Writing is celebrated as one of the fundamental artistic forms of human expression. Like our rich emotions, literature takes different forms to satisfy our need to define our identities and shake our understanding of nature and reality.

But what is enthralling in literature is its inherent quality to connect minds, from authors to an audience anywhere in the world. A string of words, a collection of paragraphs, or a melody of lyrics carries a vivid mixture of ideas flowing from the imagination of its creator. How an audience interacts with these forms is as magical as their creation.

The Hurdles of Student Potential in the Digital Age

“Imagine if you couldn’t talk. It would be hard to express those deep feelings,” 10-year-old Shiraz Rothschild told beijingkids, “Writing is a form of art because you’re trying to express yourself just like what the early cavemen did. Instead of making sounds, they drew and that’s what’s probably more affectionate and personal.” The Grade 4 pupil at The International Montessori School of Beijing (MSB) is one of the students who wrote a collection of literature as part of the school’s literacy program. “[But] since we have computers and technology, you can remember quotes or Google something,” she continued.

Whereas technology has opened many new channels for self-expression, it has a detrimental effect on people-to-people interaction. “It seems that people have lost their humanistic side in this digital age and conversation have been replaced with [short-form] messages or emails,” said Kaersten Deeds, university counselor at Dulwich College Beijing (DCB).

Student literature is mostly published in-house.

Today’s messaging methods have brought that impulse for swift responses, which are more often laconic and prone to misinterpretation. When what is viewed as a facilitator limits personal interaction, we wondered how it would affect reading and writing.

“The limitations in conversation have plagued many students who are a part of this super digital generation,” Deeds said. “They have lost the ability to communicate effectively and advocate on their behalf. There are a newfound shyness and awkwardness attributed to human interaction that can now easily be masked by [short-form] text.”

Students are also prone to look for simplistic answers while discovering their own voice. Simon Shieh, one of the editors of Beijing Youth Literary Review (BYLR), said that youth have a hard time seeing the larger picture. “[They] are constantly looking for the right answer and that’s a bad thing to do when you’re writing creatively or what you’re writing about is a kind of expository essay, or just making an argument. A lot of times in writing there is no right answer. I guess that might be something that holds students back nowadays.”

That difficulty in self-expression can be attributed to the dilemma of finding an identity, especially for students. There’s so much noise in the background and more often than not, youngsters try to conform to whatever is the norm or prescribed by society. When students write essays for school tests, preparation for university, or to express themselves, Deeds said they follow the superficial, use a complex jargon, or discuss a hackneyed theme. The combination results in a stagnant and bland story that shows no deep thoughts or fails to reflect their character and potential.

Creating a Student-Led Narrative

“Children are storytellers, negotiators, and reporters. They’re all of these things,” said Colette Cooke, lead teacher and deputy academic head at MSB. Cultivating their inner selves, as she said, is done through motivation. But in writing, a crucial factor is not just motivating but also valuing children’s contributions. “No matter what they write, read it like it’s gold, showing them that you value their voice and that there are different ways to communicate with their audience.”

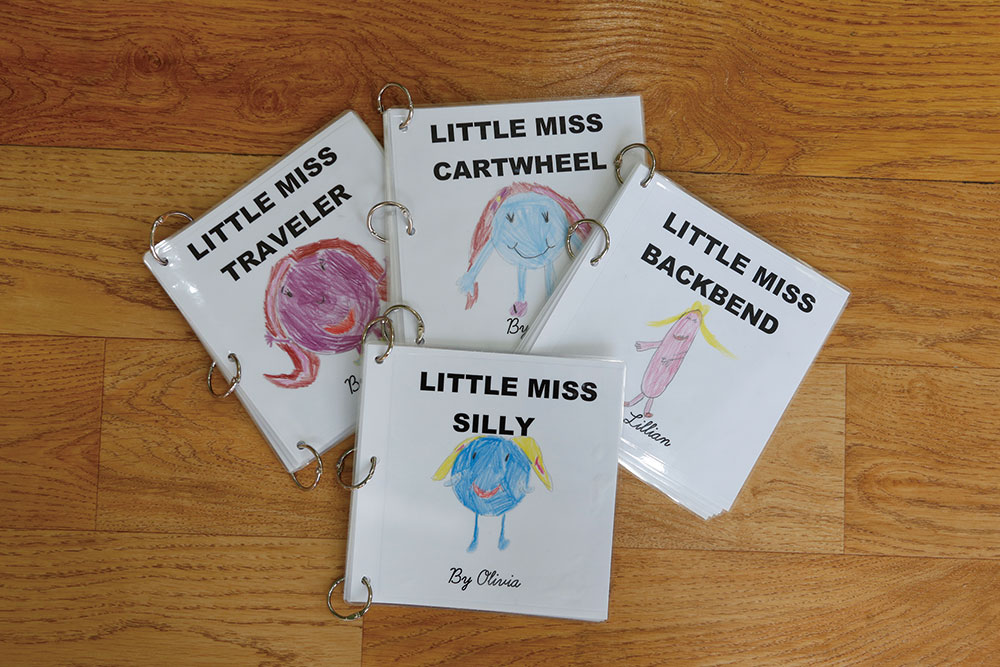

Rothschild told beijingkids she has written four books and a number of poems as part of MSB Authors, a platform under MSB’s literacy curriculum that allows students to author books and compose poems and other literary works. All the compositions are put in MSB Authors Corner in the library and in every classroom for other children and visitors to enjoy.

“It was impressive! If I didn’t put my name next to it, my family probably would think that it was written by someone else,” Rothschild said of her very first book about herself, published when she was grade 1. At the time of writing, Rothschild is creating her fourth book, about Greek mythology.

The platform, as MSB calls it, is a concept initiated by their student Catherine Ma and her mother last year. In April 2017, we featured Ma and how she authored a bilingual book that compiled years of her literary work at the school. MSB developed the concept and integrated it into their English literacy program. Cooke said the platform nurtures student authors in this age of technology by going back to the roots of writing: knowing first their interests, and then teaching them the underlying skills in writing and publishing, and exposing them in different literary genres. The outcomes come in the form of books: poetry, biography, and fiction. Since the launch of MSB Authors, the school has seen a continuous stream of literary production from students.

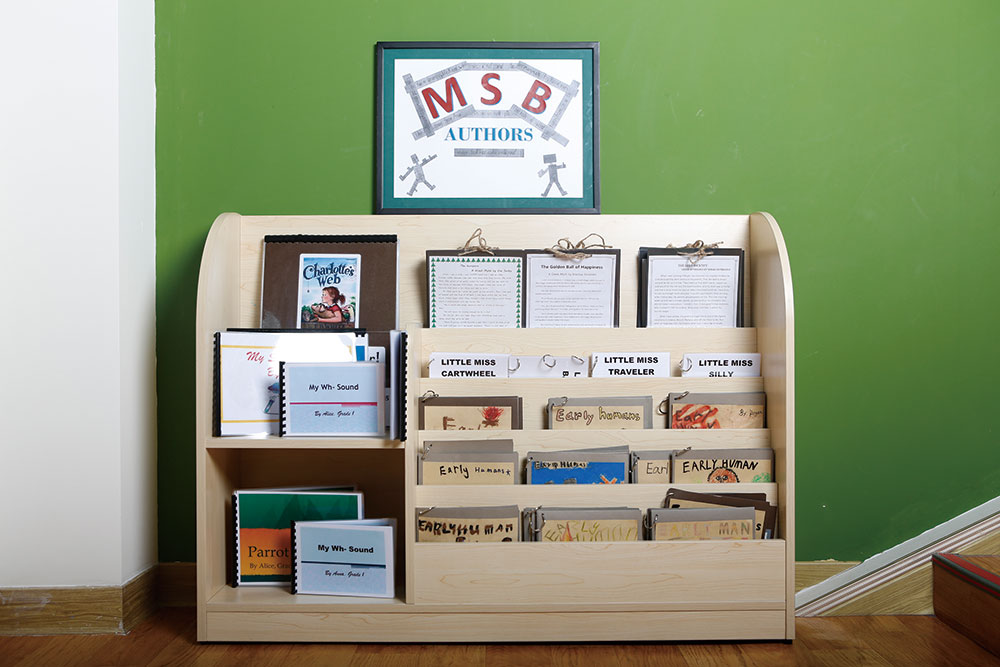

“My philosophy is that the books that our children read in the library are no more valuable than the books they produce themselves, or the things they have to say,” Cooke said. “When we offer children an idea or experience, the directions that they go in are endless.”

Corners such as this appear in the library and every classroom.

Real World Opportunities for Young Writers

When given an opportunity, young people can create colorful and perceptive personal narratives through writing. “[That] identity can help you feel like you’re something… not defined by your grades, depression or anxiety, or your parents,” Shieh said. “Some teenagers are timider and they will not tell their stories, but a lot of other teenagers are just burning to tell someone [their narratives]and to be taken seriously, [and]that’s the thing that BYLR does – to take young writers seriously.”

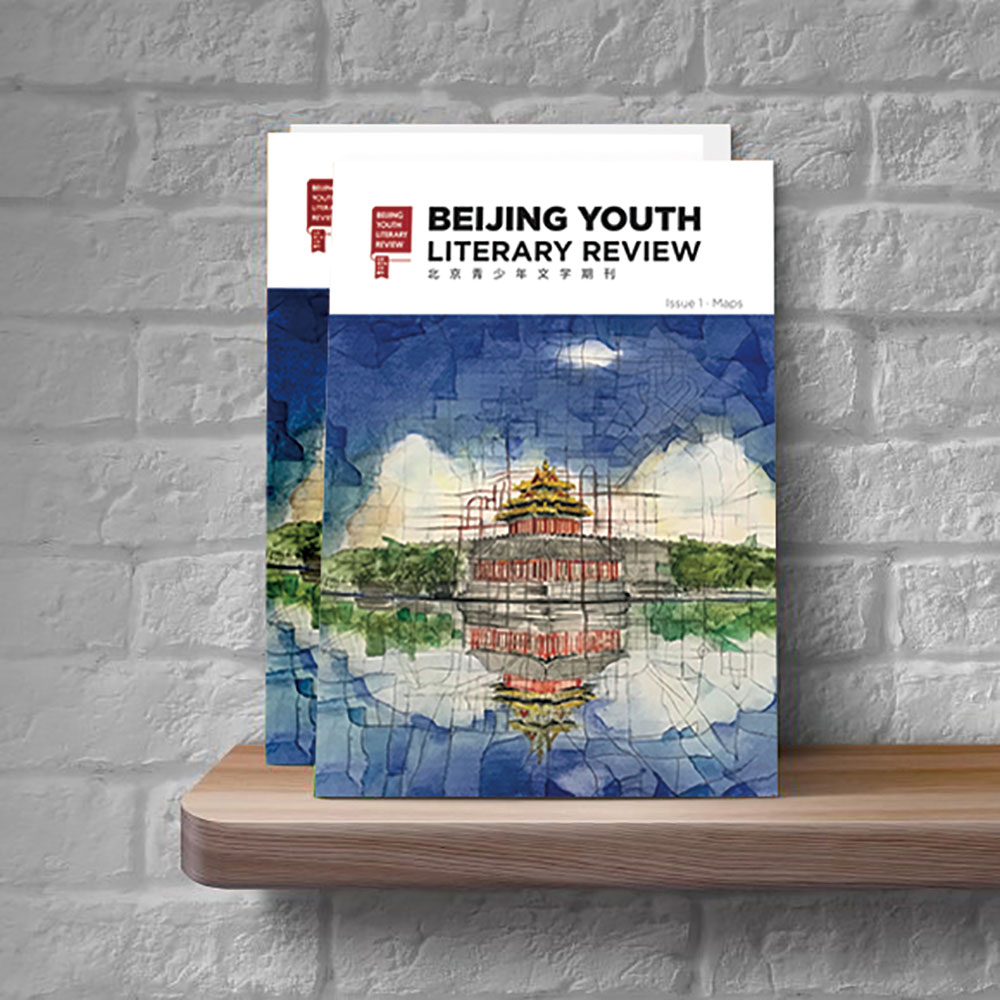

In Spring 2017, Shieh and colleagues Kate Rowe and Jennifer Fossenbell launched the first issue of BLYR, Maps. It featured 40 student writers from different schools across Beijing, all of them giving a perception of the ethereal territories of childhood and growing up.

“It’s such an empowering tool [and]feeling for a young writer to have this platform … and be taken seriously as someone who has an interesting story.”

Preparation for Life and Study After Grade School

Shieh said BYLR not only gives personalized feedback to budding writers, but also readies them for college applications, helps improve their creative and technical writing skills, and fosters a creative literary and artistic community of young people in Beijing.

But what is important, as he said, is to let young people vent out and let their voices be heard through writing. “There’s always going to be people who need to create narratives out of their experiences, their lives, as a kind of catharsis or a way to solidify their identity.” Shieh believes that it is important for educators to teach young people the craft of writing to help students to liberate their voices without getting stuck in the notions of what is right or wrong, or good or bad.

Cooke, meanwhile, said that elementary children need to be exposed to hands-on and collaborative activities with older peers so that they will be motivated to write as part of holistic learning. Most of the time when students share their literary work, she explained, they become enthusiastic to the point that they want to write more. “We’re a Montessori school and we teach in multiple age groups. And that’s exactly why we do it. Younger children learn best from peers that are slightly older than them. And it just develops so much community in the school to do that.”

The proud work of the Beijing Youth Literary Review

Words from Within

Rothschild shows no sign of stopping her literature production. “I will still write books, but the books will probably be very different. When I look at the journals [I made] when I was in first grade … it’s also like saying how good you were at that age. When I think of them, I’m like ‘I was so little, I was so young, everything wasn’t that good.’ But when you look at it now, you’ll be like, ‘Wow, I was so mature and big.’”

Both Cooke and Shieh believe that writing comes from the unconscious, and it is important young people be invested in it so that they can amplify their voices, exude their identities, and express their emotions. When someone understands and relates to that voice, the writer succeeds in producing a powerful piece of work, Shieh said, while Cooke calls it “magical” and a “quintessential thing about being a human.”

“If you lose the ability to speak,” Rothschild said, “… it’d be hard. But I think I can go a whole day without speaking and just showing my emotions, like happy or sad. Because people, humans, basically depend on emotions. Words are the connections from emotion to emotion. If you didn’t have emotions, there would be no use for words.”

Featured image shows Colette Cooke (left) who has encouraged Shiraz Rothschild (right) and other MSB pupils to author literacy works. Photos: Lens Studio and courtesy of Beijing Youth Literary Review.

Download the digital copy here.