The rivalry between Beijing and Shanghai runs pretty deep; it’s like Tom and Jerry, Ali vs. Frazier, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh. Beijing is the political and cultural capital of China, while Shanghai leads on finance and fashion. Beijing has smog, Shanghai is smug. And so on.

There’s no doubt which side we here at beijingkids fall on – the clue is in the name. However to live in China and not experience one of its great cities would be taking civic loyalty a step too far. So Andrew Killeen and his family set off for the town once known as “Little Suzhou,” to see what it has to offer.

Our previous visits to the Shanghai Science Museum and History Museum had delivered mixed results. However China’s second city still had an ace up its sleeve. Its Propaganda Museum was one of the most fascinating exhibitions I’ve seen, not just in China but anywhere in the world.

The Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Center, to give it its proper name, is a private collection hidden away in the basement of a residential compound, and is not easy to find. If you’re traveling by subway, the nearest station is Changshulu. Take exit 8 and head north, but don’t go all the way to Huashanlu, which will take you round a lengthy detour; instead turn left down Changlelu, and the entrance to the compound will be straight ahead of you at the junction with Huashanlu (look for the number 868 on the gate).

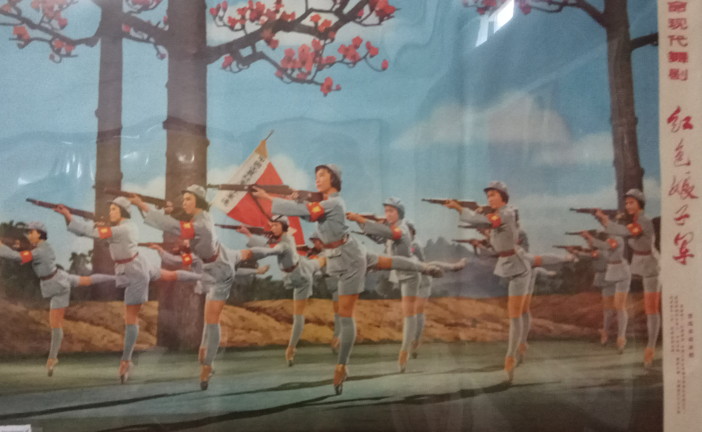

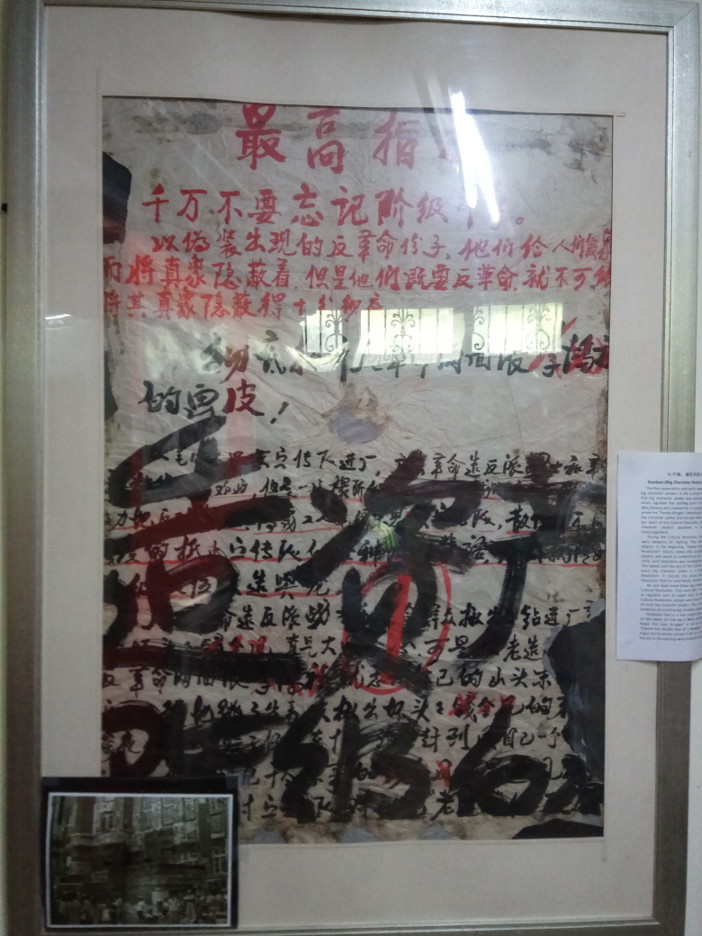

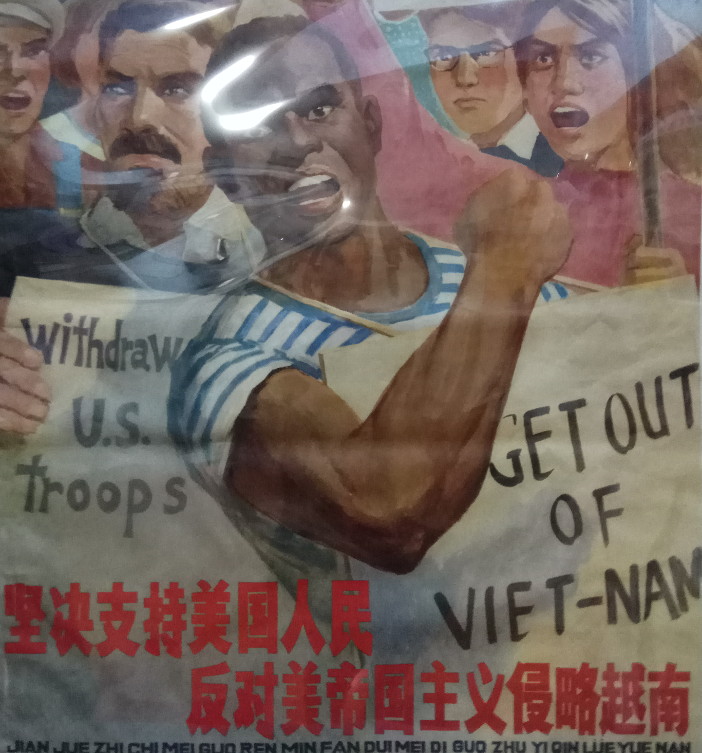

Once you’ve tracked it down though, a unique collection awaits you. Under Deng Xiaoping’s reforms the propaganda posters of the past were banned and mostly destroyed, so surviving examples are rare. However they take you on a unique journey through the 20th century history of China. Beginning with anti-Japanese posters from the war, you pass by the Korean war, the Great Leap Forward, the Vietnam war, the US civil rights movement, the Cultural Revolution (with its “big character” posters”), and the post-Mao struggle for supremacy.

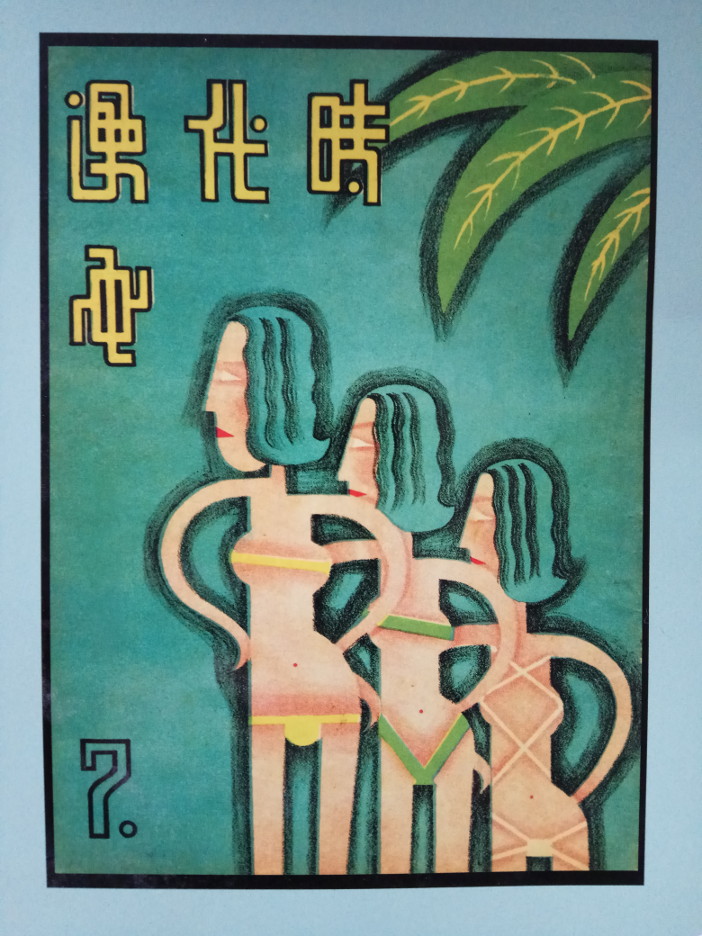

As with many Chinese museums, there’s a charming haphazardness about the exhibits. As well as the propaganda art, there’s memorabilia, and a selection of “Shanghai Ladies”, pretty, chocolate-boxy posters used in advertising. Most are quite demure, but one or two were clearly pushing the limits of what the censor would allow. There are also some startling examples of Modernist paintings, which show that the energy and creativity of the art scene in China in the 30s were as strong as anywhere in Europe or the US. Many of the artists involved went on to work on propaganda posters.

Not all the posters are as well presented as one might hope, being displayed behind dirty sheets of plastic. And one can only hope that this irreplaceable collection is protected by adequate fire safety provisions.

As a family-friendly attraction, it’s perhaps best suited to older children: my history-mad 11 year old was engrossed, but my 8 year old sat on a bench impatiently waiting for us to finish. He had to wait well over an hour, as the exhibition is deceptively large. I would advise too bringing some money for the gift shop. I’m not generally a purchaser of souvenirs, but you’re likely to want to buy some of the reproductions or even original posters on sale. Whatever you do though, if you visit Shanghai, you should not miss this unique exploration of China’s art and history.

Photos: Andrew Killeen