As a self-confessed geek, I feel like science can be overwhelming to a lot of people. Science journalism and reporting might be the most boring stuff people can read but for young minds, it means a lot. Ever wondered why the dinosaurs got extinct? Or, how about why massive solar flames can be harmful to your skin? It’s never easy to understand such things especially when they sound so daunting.

But don’t get me wrong, science journals are like novels or any other good read — though it takes time and skill to understand the complex statistics or “scienc-y” language. So in Fantastic Subjects, a series from our sister magazine JingKids, we bring scientists to tell us how science can be so much fun by making out-of-this-world concepts easier to comprehend.

We start our first Fantastic Subjects looking above and seeing the stars with the help of astronomer Richard de Grijs. He’s also a professor of astrophysics at Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics and at Peking University.

Richard de Grijs

What’s it like to be an astronomer?

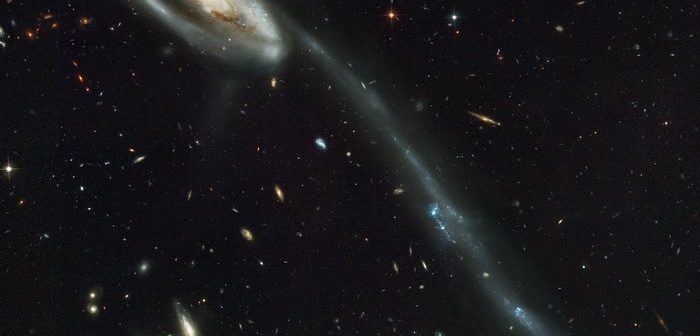

I am an astronomer. That means that my team and I study objects you can see – often only with a telescope – in the night sky. The objects we are interested in are very large groups of stars that all clump together because of gravity: all these objects attract each other, so you get nice round “clusters”. These clusters form in the most violent environments in the Universe. Think about collisions between galaxies similar to our Milky Way galaxy, or enormous “bursts” of new star formation in galaxies. To see the clusters we are interested in, we use large telescopes on Earth and even the Hubble Space Telescope, which is orbiting the Earth a few hundred kilometers above us.

What does it involve in terms of daily tasks, resources, or people interacted with?

My team consists of a mixture of undergraduate students, Ph.D. students, a few research fellows (called “postdocs” because they already obtained their “doctor” degrees) and many collaborating scientists from both inside China and abroad. Most of our work does not involve looking through telescopes, but working on our images and other data on computers. Images alone don’t tell you very much about what is happening to our objects; we need to be smart and try to understand the physics at work. We do that by looking at objects at different wavelengths (“colors”), from blue (or even bluer than blue, ultraviolet) to red and “infrared,” heat radiation that we cannot see with our own eyes (but some animals can). We analyze the images in the computer, where we “simulate” the conditions in space and then we apply the physical processes we think are important to see whether we can recreate what we see in the sky. So, really, it’s a lot of careful bookkeeping, “statistics,” and working with lots of numbers.

What are some of the interesting projects you have undertaken on this subject?

There are a few main topics my team works on:

We use the star clusters we are interested in as components of the galaxies they reside in. Because large star clusters only form in violent environments, if we can work out how old they are, we can use that information to determine when our galaxies were involved in collisions or other such events. One of my Ph.D. students is now working on large star clusters that are found in beautiful “rings” around the centers of some galaxies.

We are also interested in what star clusters are made of. But to see the individual stars, you need very good telescopes and equipment, ideally above the Earth’s atmosphere (which makes stars look like blurry images). Because star clusters like the ones we study contain millions of stars, we can use them to understand how stars themselves form, and what happens to them when they grow older. And in addition, because they are so close together, we can also study how they affect each other. My team is particularly interested in what we call “intermediate-age” clusters, which are about 1 to 3 billion years old; that’s not very old compared to the oldest stars in the Universe, which are close to 13 billion years old. Unfortunately, such intermediate-age clusters are not available in the Milky Way, at least not very large clusters, so we have to point our telescopes at some nearby galaxies, called the Magellanic Clouds.

A more recent project we have been working on very hard is trying to understand all kinds of stars that show changes in their brightness, so-called variable stars. They can be used to determine distances in the Universe, and we are working with both domestic colleagues and collaborators in Japan on a better understanding of the three-dimensional structure of the Milky Way galaxy using such variable stars.

Finally, I am working on a book about a topic in the history of science, specifically the determination of longitudes at sea. That’s a very different topic, but it relates to astronomy because they used to use eclipses of the Moon or the motions of Jupiter’s moons to tell the exact time you need to work out your position at sea based on the stars. This era is a really fascinating period in the history of science. I recently completed a section about the famous Chinese Admiral Zheng He, whose Ming dynasty expeditions contributed to progress in this field.

The star-forming region NGC 3603 – seen here in the latest Hubble Space Telescope image – contains one of the most impressive massive young star clusters in the Milky Way. Bathed in gas and dust the cluster formed in a huge rush of star formation thought to have occurred around a million years ago. The hot blue stars at the core are responsible for carving out a huge cavity in the gas seen to the right of the star cluster in NGC 3603’s center.

What are some of the most memorable/unforgettable experiences and places associated with astronomy?

I am very lucky to be a professional astronomer because I get to go to the most beautiful places for my job. These include observatories on mountaintops in remote regions, like the summit of the highest volcano in Hawaii and remote mountains in northern Chile. Going out at night in a really dark place and looking up at the night sky is truly awe-inspiring – it makes you feel really small, and you really appreciate the beauty of the Universe. I am currently in New Zealand, where I recently had the opportunity to look at some very special objects in the southern sky (not visible from Beijing) through a telescope with a diameter of 1 meter – fantastic images, a really good experience!

I have also been to observatories on islands in the Atlantic Ocean – the Canary Islands – and in the southern United States. My current stay in New Zealand is also job-related: I received an Erskine Award from the University of Canterbury, so they invited me to spend almost 2 months here in a very beautiful environment. Perhaps the most interesting place I’ve been to as part of my job was La Reunion island, a French territory in the Indian Ocean, where I attended a conference a decade ago. At that time, I was based in the UK, and so I flew there via Paris, an 11-hour domestic flight!

How has this subject changed your perspective?

As an observational astronomer, you will at one point or another be awed by the vastness and the beauty of the Universe, and realize that we as humans are really small fry and not that important in the grand scheme of things. I think that I am more level-headed now than I was when I was younger; I can see the relative importance of things better. Also, in astronomy, we deal with big numbers, and that is not something that scares me – perhaps a good thing too!

Located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of our neighboring dwarf galaxies, this young globular-like star cluster is surrounded by a pattern of filamentary nebulosity that is thought to have been created during supernova blasts. It consists of a main globular cluster in the center and a younger, smaller cluster, seen below and to the right, composed of extremely hot, blue stars and fainter, red T-Tauri stars. This wide variety of stars allows a thorough study of star formation processes.

How did you come to the point that you can do astronomy? What knowledge, skills, or experiences would be necessary?

It started quite a while ago, already at primary school around the age of 8. I was really quite into learning about astronomy then, and it turned out that I was quite good at maths and physics at both primary school and high school. Those were, in fact, my best subjects at high school, so the step to studying astrophysics (physics and astronomy) at university was not too large. Astronomy at university and research level requires you to have a good understanding of physics and be comfortable applying mathematical equations to your data. You don’t have to like pure maths, but you should be comfortable handling equations, particularly in the context of writing computer programs to deal with your observations (or theoretical analysis, if that’s what you like more). It also helps to speak one or more foreign languages, because the field is very international. My native tongue is Dutch, but by now my first language is English – it’s that important to make career progress in our field! In addition, many observatories are actually located in countries where they speak Spanish, and I actually decided to learn Spanish for that reason – that also exposed me to more of the interesting cultural aspects of the countries I have traveled to.

What’s your family/friends’ reaction when you first decided to pursue astronomy? And now?

My parents have always been only supportive. They saw that I was good at maths and physics, and they supported me in my choices, from a very young age. They only insisted that I finish my education, at any level I studied, so that I would have a good chance to land the type of job I wanted to pursue.

What do you think to be the essence of astronomy and why should people study or work on it?

Astronomy goes beyond the niche area of the field. We educate students to become critical thinkers who are familiar with big numbers, computers, “big data,” and who can apply their skills in a very wide range of fields. When I worked in the UK, many astronomy graduates would get jobs in the financial services industry in London – and make a lot more money than me… In the Netherlands, where I am from, institutions like the Department of Motor Vehicles, the national statistics institute, and companies like Philips would hire astronomy graduates. But above all, you should study astronomy only if it really interests you, not to get some service industry job. Without a passion, interest and some talent in the physical sciences, it will be very hard to reach your goals. Follow your heart’s desires!

Photos: Richard de Grijs

See more of my stories here.

Email: andypenafuerte@beijing-kids.com

Web: coolkidandy.wordpress.com

Instagram: @coolkidandy