Despite being billed as an innovative mode of transit that will keep you safe from smog, Beijing’s new air purifier-equipped Gongjiaoyilu buses are actually a catastrophic bust.

I rode one of the shiny new bright red buses (which are electric-powered in addition to sporting air purifiers, as part of Beijing’s push against pollution) from Guomao to Tiananmen on Oct 26, when the AQI was well over 250 outside. The hype surrounding these pollution-filtering buses in state media, along with the reassuring hiss of the sealing doors, and the shocking quiet (when compared to other noisy, drafty bus rides I’ve taken in Beijing), all led me to think that the air quality inside would be fairly good. A ride on a bus outfitted with purifiers is also all the more appealing after recent news that Beijing’s air quality has worsenedin the past year, despite intensive efforts by the authorities to curb pollution. The Gongjiaoyilu fleet consists of 10 air purifier-equipped buses that run the length of Chang’an Avenue, according to Xinhua.

However, when I switched on a Laser Egg air quality reader to find out just how effective the bus’ tech was, I was surprised to see that the index never fell below 200 throughout the ride. The pollutant level shot up to 250 or more when the doors opened to allow new passengers onboard, which should be expected, but when the doors hissed shut in what sounded like a protective seal, the reading only went down to around 225, and rarely dipping below that. It certainly never fell under the “moderate” AQI 50 level that the World Health Organization recommends, making the bus promotion behind the bus line misleading at best, seeing as passengers should still wear their pollution masks to keep their lungs safe while onboard, which contradicts positive media coverage and the cutesy, clean air cartoon signs emblazoned on the buses’ walls.

That said, it’s farfetched to expect much else from a bus that opens its doors regularly to take on passengers during a run, and even more of a pipe dream for administrators to imply a vehicle could pull such a feat off. Liam Bates, founder of the Kaiterra startup (formerly Origins) that designed and sells the Laser Egg AQI monitor, says, “Electric buses are great – though you should look into how the electricity is generated – and purifying vehicles are great too.” However, he’s quick to point out: “It’s really hard to purify a space like that. You’d need a ton of power, and a very very strong purifier. Like 20 large Blueairs!”

Liam’s skepticism was echoed by Charlie Thomson, the owner at the Environment Assured home AQI assessment service, who says: “Whether in a building or in a vehicle, simply having air filtration equipment in place does not guarantee clean air. Both the equipment use patterns and the operating conditions will greatly affect the results of the system. In a bus, the constant opening and closing of doors makes it extremely difficult to control the air quality.” He adds that there are some potential solutions to the issue, such as positive pressure filtration, along with built-in monitoring of PM2.5s to show how efficient the system is working.

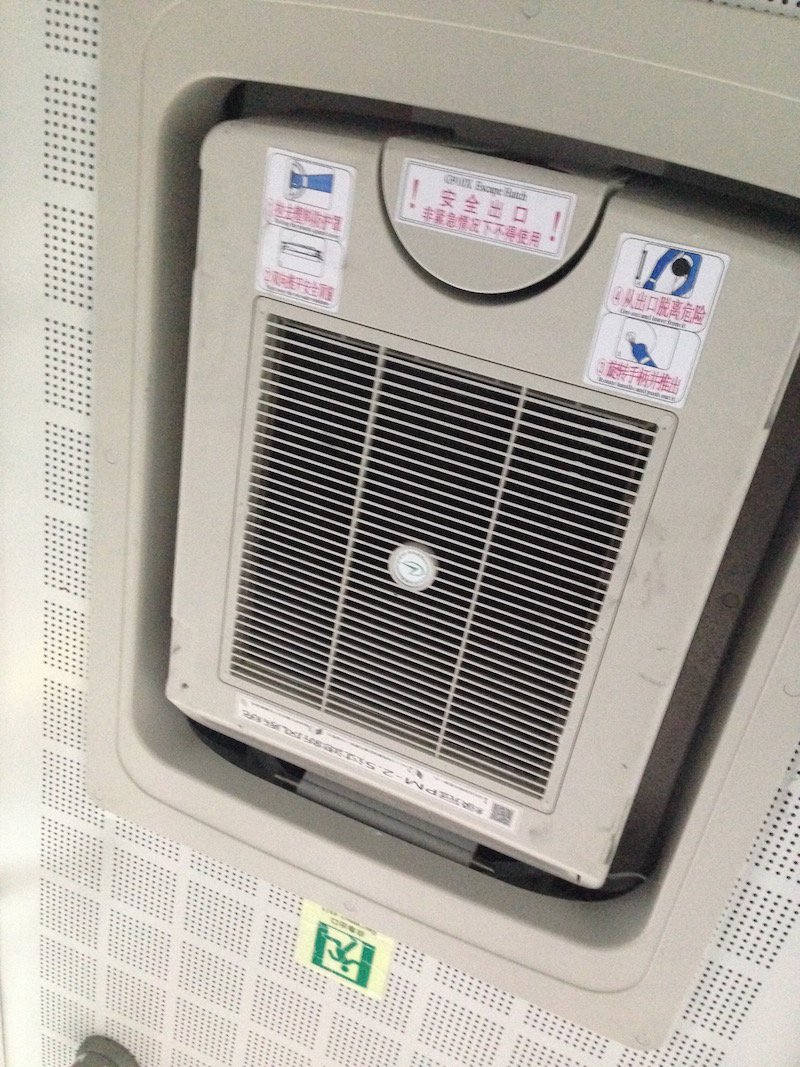

But such sophisticated features don’t appear to be in place on the Gongjiaoyilu bus. Johannes Lauesen, the CEO at Climatech (a developer and producer of air purifiers and positive pressure purifiers) says, “At first glance, I do not see that they have enough capacity for a city bus. A school bus, for example, could have a reasonably weak, 1-2000M3/h or so, cleaner to keep it clean. But a city bus would need to be able to replace all the air in the bus every 10 minutes to keep up.”

Lauesen goes on to explain some of the key issues inherent in keeping pollutants from riding along with you on a public bus: “The issue is that people and doors act as ‘pumps’ moving most of the air in and out of the bus at every stop. Another issue is if the clean air is not distributed properly, then it will only be a few bubbles that will be very clean. Just imagine how much air comes in the leaky doors while driving … Seeing the images of the ‘cleaner,’ it looks like a 500-1000 M3/h cleaner and that is far less than what is needed in such a dynamic environment.”

Although there’s the slight possibility the purifiers weren’t fully operational that day, or that they are still working out some bugs. But that’s still problematic because it indicates the purifiers are more window dressing than anything (why tout that feature in state media and then not have it ready when people hop aboard?). And it doesn’t address the problems of breaking the seal, and needing massive, and therefore probably quite large, purifiers to keep the interior smog-free.

All that said, what would be a better alternative to a transit system that overpromises with purifiers that fall short? When asked if stocking buses with pollution face masks instead of puny purifiers and doors that let the smog seep in, Lauesen admitted he’s “not sure. To be honest, I really like the idea of clean air in the bus and on all public forms of transportation. Masks just aren’t the same.”

That point makes the new buses all the more disappointing to Lauesen, because the promise of truly PM2.5-free public transit is so very enticing. “Basically they should have done some testing and maybe even used something like the air curtains in shopping malls at the doors. In my eyes, masks are for general outdoor activity, and having the chance to take them off on the bus, on the metro, and in a cab would be great.”

Photos: Xinhua, Kyle Mullin