Even centuries ago, the people of Beijing were willing to help those less fortunate, and throughout the city’s recent history, there have been many institutions providing aid to the poor, the sick, and the displaced.

In the years following the Manchu conquest of Beijing in 1644, poorhouses known as (养济院 yangjiyuan) were opened throughout the city to assist those who had lost their homes or were the victims of natural disasters. The Manchu imperial family donated lavish sums to the poorhouses, including 80,000 ounces of silver from the Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, during the great floods of 1653-1654. Not to be outdone, her grandson, the Kangxi Emperor gave over 100,000 ounces of silver during another devastating flood season in 1679.

The imperial government also operated soup kitchens (粥厂 zhouchang), which dispensed porridge and ran mostly in the winter months when there was little work, and food prices rose as the ground froze. Often based on the grounds of local temples, the gates to the kitchens would open at meal times and the needy and hungry would rush inside as the monks and staff ladled out bowls of thin rice gruel cooked in massive iron vats.

Other institutions looked after the aged and alone, a particularly vulnerable population in a society where most people relied on their adult children for support once they had grown too old to work. Many of these endeavors were organized – or at least partially funded – by the state. The imperial court often showed a reflexive aversion to charities run entirely by private individuals or institutions. They were concerned that groups providing services which should be, in a perfect society at least, the responsibility of the state had the potential to create alternative centers of power.

At the same time, officials in the imperial period were stretched thin. The government served a whole empire, and while the imperial administration was impressive in its breadth, it tended to lack depth. This meant that the government even in the best of times relied on local elites, religious organizations, and other non-state entities to provide critical services like flood relief, poverty alleviation, and food distribution.

There were also debates in government about the wisdom of welfare. Some officials argued that too much generosity encouraged the poor to become lazy and dependent. It’s refreshing to know that even 300 years ago, politicians could still act entitled and unsympathetic when it came to helping the less fortunate.

Beijing was also famous for its Provincial Halls (会馆 huiguan) where sojourners coming to the capital could rest and connect with fellow travelers from their home province. Many of these guild halls were located in the Qianmen area, and they filled during peak trading seasons or when students sat for the imperial exams. At other times, the Provincial Halls opened up their soup kitchens and “Benevolent Halls” (膳堂 shantang) that were modeled after the efforts of local elites in the provinces to give aid to their poorer neighbors. Charitable acts were one of the ways that the elite displayed their status in society.

But too often the best efforts of the state and private citizens fell short of meeting the needs of Beijing’s least fortunate. Not only floods but droughts and earthquakes, wars and rebellions, could drive people from their rural homes into the cities seeking food and shelter. Those who could find neither joined the ranks of the city’s beggars.

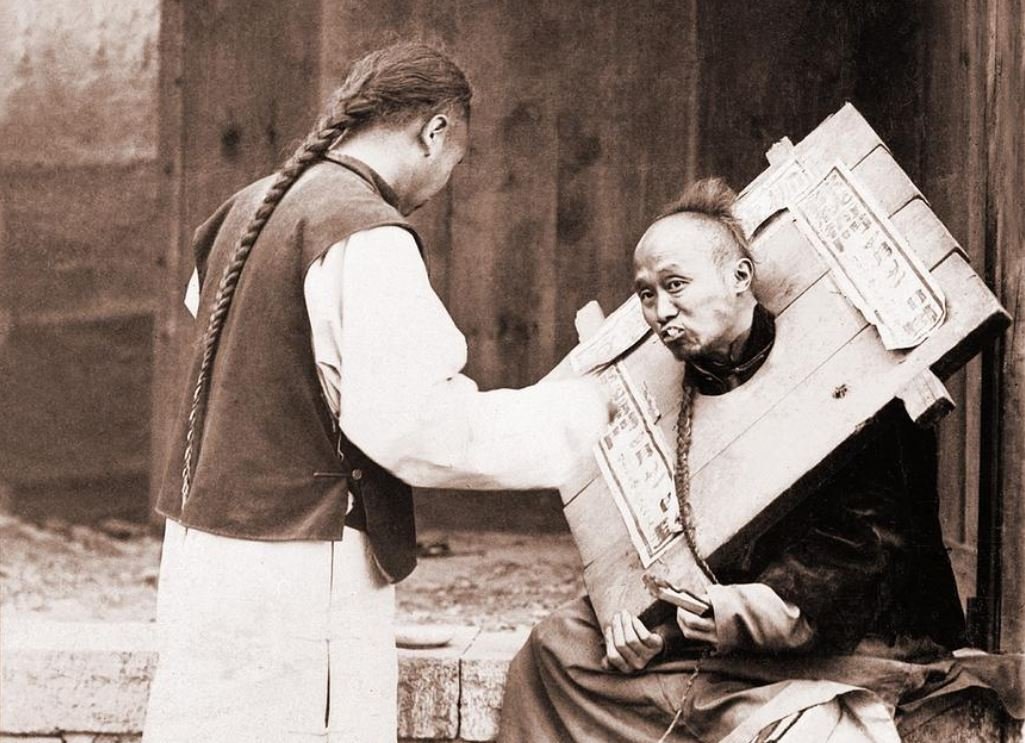

In the late 19th century, thousands of beggars of all descriptions – naked, lame, mutilated, leprous, and insane – accosted travelers and locals alike as they made their way through the streets and markets. The commercial districts near the Qianmen Gate were particularly notorious for being thick with beggars. The beggars had their own guild and guild master who settled territorial disputes and extorted money from shopkeepers willing to pay up front to avoid having the entryway of their stores blockaded by hungry vagrants.

The 19th century in Beijing also saw the introduction of a new form of charity as foreign missionaries opened schools for young, their own orphanages, and soup kitchens, as well as hospitals, and shelters. These institutions took advantage of the privileged position of foreigners, who were protected by the treaties signed between China and the foreign powers, to avoid government interference. In particular, the missionaries were well known for their clinics, dispensing the latest medicines and medical care even to those unable to pay.

While life in the capital has improved drastically for most folks when compared to previous times, today’s NGOs and charities are following a long tradition in Beijing of helping the less fortunate despite facing many challenges in doing so. While the nature of charity has changed, compassion has not. Philanthropy and activism have a history in Beijing which goes back centuries and will hopefully continue for years to come.

Sources and further reading:

David Strand, Rickshaw Beijing: City People and Politics in the 1920s

Susan Naquin, Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400-1900

This article first appeared in the Jan/Feb 2018 issue of the Beijinger.

Read the issue via Issuu online here, or access it as a PDF here.

Images: shixunwang.net, Fine Art America