2017 will largely be remembered in the west as the year the #metoo campaign came to prominence and for the many women who broke their silence on prolonged and pervasive experiences of sexual assault. While the western world was closely following the movement’s trajectory, with outrageous stories surfacing almost weekly and tarnishing the careers of many previously admired men, the chatter of sexual misconduct on the Chinese internet was notably much quieter. But that’s not to say it wasn’t having its own moment.

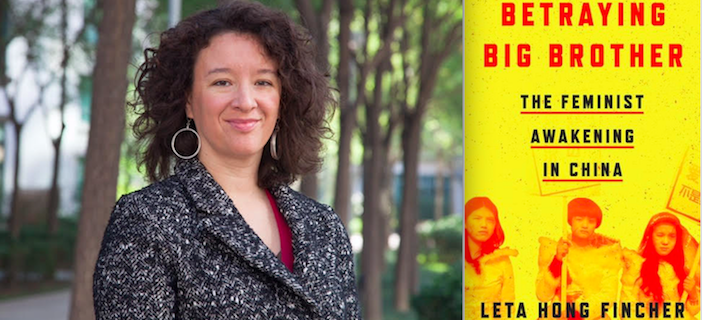

Below we speak to the acclaimed sociologist, journalist, and writer Leta Hong Fincher about her take on how views on and openness about sexual assault are changing outside of the western sphere. This year, Fincher is gearing up to release her follow-up book Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China, the follow-up to her first and widely acclaimed book Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China in 2014.

TBJ: In your last book, you wrote about the concept of leftover women in China and gender inequality mostly through the lens of what it is like to be considered “unmarriageable”. Your upcoming book Betraying Big Brother seems to tackle feminism and activism in a broader sense and in that way, what would you say is the main message to be taken away from it?

Leta Hong Fincher: Well, I don’t want to give it all away but one of the things that I write about is the importance of the detention of the Feminist Five in 2015. I followed them a lot and interviewed them and other core members of China’s feminist movement. The government launched this crackdown on feminist activism back then and that crackdown has continued to this day. I kind of analyze what is it that led up to that turning point. I also write a little bit about the history of feminism and revolution in China and what does it mean for China’s future. The rise of this new kind of political resistance in a form of feminist activism but also a broader awakening among women in China, particularly educated young women who are beginning to really stand up for their rights. You can see that expressed in the new #metoo movement as it’s developed in China with all of these largely female university students signing petitions to their universities demanding that they address the widespread problem of sexual harassment on campus for example.

I think that this conflict between the rise of feminist activism and a new determination on the part of the Chinese government to stand out feminist activism and stand out feminist movement that conflict is going to, I think, play out and be very important in coming years in China.

Fincher’s new book ‘Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China’ is due September this year

Via your research, which involves eyewitness reports and in-depth interviews with key individuals telling their very personal stories, you also touch upon the #metoo hashtag coming to China. Have you seen any large changes in the four years since your last book came out regarding how women and greater society view sexism in China and how people now approach feminism?

Yes, there wasn’t a great deal of awareness about feminism at the time I finished writing in 2013. There were these feminist activists who were engaged in various kinds of imaginative performances and art protests about women’s rights, but they were not attracting a lot of attention at that point. So they were mainly kind of isolated individual actions. This is why I believe that the arrest and jailing of Feminist Five in 2015 an important turning point for women’s rights because before that, overall, I would say that up until then women who went to university and were beginning to carve out their careers were not really aware of a need to fight for their rights. I write about that a lot, particularly when these women are getting married and buying housing, that they make a lot of compromises and they don’t have a sense of solidarity with other women who are really fighting, or not really fighting, but there wasn’t really a collective sense of a need to fight or stand up for their rights. That has really changed in the last few years even though I would say there is still a problem, which isn’t unique to China either.

You know, a lot of women still don’t recognize their own oppression and that is a phenomenon you can see around the world, it’s not unique. There really has been a shift in consciousness overall among these young, educated women in particular. It’s pretty dramatic actually, that the number of women who are being very vocal on social media about sexism or misogyny. So I am not only talking about hardcore feminist activists who are political activists who get into trouble with the police. I think there is a broader awakening among a lot of women in China. That’s very different from just five years ago, which is when I was doing my research. Which is why you see something like what is expressed in #metoo movement. Even though you don’t see the hashtag going viral in China, of course, that is because the widespread internet censorship, but what is happening is already pretty astounding. The fact that there are all these students at dozens of universities who are using their real names to sign petitions, to speak out about sexual harassment. Those people who sign petitions are taking a real risk and a lot of them are being questioned by somebody about why they are signing the petition. You know, every single one of those people who has signed the petition on sexual harassment in China is taking a personal risk. It’s much riskier than for, let’s say, an American woman to just tweet #metoo about her personal experience.

The fact that that is happening in all these different universities in different parts of China really suggest that there has been a real shift in consciousness. That doesn’t necessarily mean that all these women who are taking action will then describe themselves as feminist because the term feminism itself has become kind of politically sensitive. If you look beyond that term, if you just look at the numbers of women who stand up for equal rights with men and they want equal treatment, they want justice, they don’t want to be discriminated against there is a real shift in consciousness.

Obviously, women activists and women in China are generally presented alongside different circumstances and, as you say, it’s not so easy for them to come out and express their experiences and their beliefs. With the Feminist Five arrest being a big turning point as well as the rise of the “rice bunny” #米兔 hashtag (China’s version of #metoo) and various petitions, do you think we are soon going to witness a breakthrough in feminism in China or do you think it is going to be a long and vicious cycle of activism and silencing and so on.

I think that what is already happening in China is extremely important. I certainly don’t expect masses of women to march in the streets, I mean that’s basically throwing away their entire futures. Although that being said, Reuters reported that there were students in Beijing who planned a street march about sexual harassment. They interviewed students who planned a march and then they canceled it because, of course, the universities warned them not to do that because it was too dangerous.

What is happening right now is extremely important and of course, the government is already trying to stamp it out but it’s very difficult. This is not the same as a handful of dissidents calling for democracy because it’s so broad and therefore much more difficult for the Chinese government. These kinds of problems – sexual harassment, sexual assault, that rampant gender discrimination at universities and the workplace – all of profoundly affect every woman and China. You can see that there are so many women who are upset about the current inequality, so it is tricky. It’s not something that the government can get rid of by jailing a handful of the feminist activists, which it already did in 2015, and which didn’t work. If anything, it may have provided more fuel and got more women interested in feminism by just enraging so many people.

In that sense, it’s going to be a long, protracted conflict I think. One of the reasons the Chinese government is cracking down on feminist movement is not just because they are organized political activist, but it is trying to push these educated women into getting married and having children. That aspect of the government goals is still the same, same dynamic that I wrote about in my book Leftover Women.

In my first book, I write about this propaganda campaign stigmatizing these women, calling them leftover, trying to scare them into marrying. The propaganda is somewhat different today, it’s taken a different form, which is abolishing the one-child policy. Now they have the official two-child policy, so it’s a pro-natalist policy now, it’s very explicit. The government is targeting urban, educated women, trying to get those women to marry and to have two children as soon as possible. So far, I don’t see any signs that it’s working, so this is going to be a major conflict between the government and between young, educated women in particular. With all of these major demographic problems that China is facing, where the population is aging, the birthrate is falling and the labor force is shrinking. This is why the government is pushing women very hard to have babies but that pressure is not working. I’m sure that this is going to be a conflict over the next few years into the future and how it is going to play out. It’s not something that the government can control very well.

As we can see, there are a lot of small details as to why feminism is so unwelcome. It’s very mobilizing and it’s very powerful in that sense, as you said, but also, it seems to be questioning the very fundamentals of Chinese society where men are in power and possibly even targeting very specific men. For instance, as with #meeto in the west, perhaps we’ll also see the targeting high-ranking men, for whom everything can tumble down if their respect is lost.

Of course. If you just look at what is happening globally with the #metoo movement. It has actually caused some very powerful men in a lot of different industries, from Hollywood to journalism to politics, it has caused them to lose their jobs. Now there is a very strong backlash in a lot of countries to the #metoo movement with people warning that it is going to get out of control. If that’s the discourse that’s happening in open, democratic societies, just imagine what a movement like that is to fundamentally one-party dictatorship in China. Just imagine how threatening that must be when communist party leaders look at what has happened with #metoo, the last thing they want is chaos.

The nexus between power and subordination and exploitation of women is a very tight link. So that movement, more broadly expressed, women’s movement, like any kind of collective action calling for more rights in a very close authoritarian society, like China, is going to be seen as a threat. This is also a very complicated threat, it’s not something easily controlled, where you just target a handful of people and throw them into jail. There is a real risk for some of the most prominent feminist activists but aside from that, you know, the government can’t control a broader kind of women’s rights movement. They have to use more subtle strategies, they can’t just use the iron fist and then just threaten all these women. That’s not going to work.

As you said before, your upcoming book Betraying Big Brother is very much based on interviews with the Feminist Five and other activists and women. You’ve talked a lot about how they are risking a lot of things simply by openly talking about their beliefs and activism. Did you find it was difficult to find women who willing to discuss their beliefs candidly?

Let me just say that it’s not that ordinary women can’t talk about their beliefs. It’s when you take a kind of political form of action. When you are in China and you sign your name to a petition calling on your university to address sexual harassment, that is a political act and that is a risky political act.

With regard to interviews that I did, I include some ordinary women who were not feminist but I do take a much more of a focus on the political activist side of feminism. No, it wasn’t at all difficult to talk to these activists and most of the activists that I interview in the book use either their real names or nicknames that they use in public. Not all of them, but almost all of them. These women are really fervently committed to the feminist movement and the government is not going to be able to shut them up. There may still be another very serious crackdown on these feminist activists in addition to the persecution that they are already experiencing day to day.

This is the underlying forces unleashed by the feminist movement. They indicate a much broader form of social change. So really what you are seeing is a shift of consciousness among a critical mass of urban educated women. They are going to pose a real challenge to the government going forward. Most of these women are not going to be content with just staying silent anymore and just putting up with widespread harassment and inequality. I think that in the future these women are going to pose a very complicated political challenge for the government.

Leta Hong Fincher’s new book Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China is due to be released on Sep 25, 2018. You can pre-order the book on Amazon and Barnes & Nobles.

More by this author here.

Images courtesy of Leta Hong Fincher