When I was around four years old, I got held back a year in school in the Netherlands. They call it having an extra toddler year. I was not quite ready to enter full-blown education, returning home after spending some years as an expat in South America. So when it got to the time where I would learn to read and write, I was a year older than the other kids.

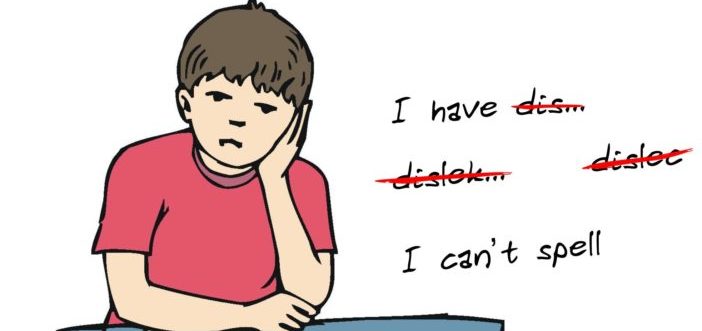

My mother slowly started to see that I was having difficulties with spelling, and as she is also dyslexic, she had some understanding what I might be struggling with. However, my school in the Netherlands did not recognize that I needed extra testing and help, so my mother fought a long battle to get me diagnosed. Meanwhile, many teachers just thought I was lazy and too busy being social in class. Before moving on to high school, my problems got serious, and finally, I got tested and diagnosed with dyslexia. I was rewarded with extra time on tests, but nothing else. Educators thought that extra time on a test would make me less “word blind.”

Here, I felt lost even in my own language. Speaking and reading were not a problem for me; though, when I had to write things down, I had no idea how words were supposed to look. In Dutch grammar class, I once had a test on which I scored so badly that the teacher made me retake it. I was sitting alone in the class while the words were dancing in front of my eyes. I did not know what to do. The more I looked, the less sense it made. But I had to escape the classroom, so I decided to make up the answers, and I randomly picked from the multiple choice, scoring an even higher grade than some of the best students in the class. I never told the teacher, but I cried alone in the toilet of an empty school as everybody had already left.

There was no way that I could stay here, so I transferred to another school. But the damage was already done. My confidence had taken a big hit. I had gone from being excited about going to high school, to being scared of taking tests. Having extra time only made me more nervous, as it gave me more time to confuse the grammar and wording.

It was at this new school that I started hanging out with the “wrong” crowd. Despite not having good grades I made many friends, good and bad. My second year in high school went horribly wrong when the teachers decided that I should not pass to the third year, but do the second year again. Only one of my teachers was opposed to this because he knew it would break me. And it did. I had no desire left in me to spend my time with kids who were two years younger. My personality was already much more developed. I had enough. The second time through the second year of high school was the hardest. I started to skip classes, especially if teachers were boring or if it involved grammar. Though funny enough, I would still go to classes that interested me. I was wild like that.

It was at this time I started my first weekend job at a department store, and soon after at a brasserie as a waitress. I could never have known how this job would be my saving grace. The clock was not my problem anymore, and I would lose track of time working for 12 hours each Saturday, serving people food and making coffee.

It may seem like a pretty dumb job, but I savored each moment. Things like making cappuccinos came second nature to me. Then moving on to the kitchen, the joy and passion I found there was something I had never experienced. I could actually hold down a busy lunch rush, all the while smiling and enjoying myself. My brain finally worked the way it was supposed to.

I was 21 years old when I moved to Houston, Texas, where my father entered me into culinary school. I quit my job and moved many miles away from Holland, the country that I felt failed me in my education. I was scared about going to college. I had never gotten good grades in the past, but when I put on those chef’s whites, I thrived. I had a bit of an advantage over the students who had never seen a kitchen, and I ran with this. Also, I was a bit special, as my English speaking and writing was not the same as the Americans I went to school with, but this time I had the reason of being Dutch and being dyslexic moved to the background.

Suddenly I was the best in the class, and people wanted to be on my team. People asked me for the answers on tests. This was something entirely new, and I even entered several cooking competitions and won all of them. The clock was not my enemy anymore; it showed me how much time I had left to cook a dish or finish my recipe.

Funny enough I have written about these experiences in Dutch on a blog, and my mother saved all of these.

They were funny and witty, though not always correct in spelling or grammar. My mother saw the value of my writing. Throughout this time I also never stopped reading. Somebody once told me when I was a child that if I read a lot, my dyslexia would go away. I believed this, and slowly got addicted to reading magazines and books.

Life has funny ways of leading you to the different paths you need to take to be happy. After finding my husband in Texas, moving to London where I became a mother, and then moving to Beijing, I picked up a magazine and saw that they were looking for parents to work for them. I thought, “I should try… stranger things have happened.” This was when I got hired to be one of the editors of beijingkids. My colleagues have patience and fix my work before the rest of Beijing reads it. So far, I have written over 200 blogs and magazine articles in a year.

Dyslexia means for me that I will never be good at grammar, but I do thrive in other aspects like cooking and public speaking. I am very artistic and have a great eye for color. I thought when I was younger that dyslexia would be the end of my education and career, but funny enough; it wasn’t. It gives me inspiration and strength to be extra good at other things, and to keep on learning and practicing with my writing.

I have learned many things from my educational journey, including that having a happy and healthy child is more important than high test scores. Those moments sitting alone looking at test questions made me lose confidence as a child. It made my journey in becoming a well-rounded adult painful and stressful. But most of all, it made me learn that anything is possible in life, and this comes from a writer who is more dyslexic than you could ever imagine.

Photos: Pauline van Hasselt, ritutorial.org

This article appeared on p52-53 of beijingkids March 2018 issue.