“You’ve never heard of biang biang mian? It’s really famous.”

My kids’ incredulity was genuine. Their knowledge of Chinese culture has long outstripped mine, just as their knowledge of the language has. Noah was even able to decode the signs which showed the small, anonymous local café served Shaanxi cuisine.“It’s called the Qin Café. Qin was basically Shaanxi. And that’s a picture of Shihuangdi. His capital was Xi’an.”

Memories of our visit to the terracotta army returned, and everything fell into place.

“Then we’d better try some.”

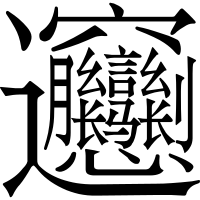

The character biáng

Biang biang mian is a particularly wide, thick noodle, characteristic of Shaanxi cuisine. While we were waiting for our food to arrive, the kids pointed out a huge, horrendously complex Chinese character on the wall. The character biáng in its traditional form takes a ridiculous 57 strokes to write, but in the simplified version needs a mere 43. It’s reckoned to be the hardest character to write, though I’m very fond of dá, meaning “the appearance of a dragon in flight.”

Dá, the appearance of dragons in flight

Not very useful perhaps, but very beautiful.

So what does biáng mean? Well, it has no other meaning, and is only used to describe the noodles. Some say it represents the sound of the cook slapping the noodles on the table, or the lipsmacking noise of customers eating it.

And the character? That’s a mystery too, though there’s a popular story to explain it.

They say that a hungry, penniless student was drawn by a delicious smell, and found a cook preparing a noodle dish.

“What’s that?” the student asked, and the cook replied “Biang biang mian”.

“Do you know how to write it?” the student said.

The cook shook his head.

“Then I’ll teach you,” the student said, “but if you can’t copy it, I get a bowl of noodles for free.”

The cook agreed, and the student then wrote a character so ridiculously difficult that he got his meal for nothing.

It’s also said that Li Si, chief minister to Shihuangdi, invented the character. But it’s far more likely that an enterprising noodle cook came up with it as a publicity stunt. If so, it certainly worked.

Our noodles came in a bowl with meat and vegetables, looking a little like bibimbap. It had the fiery red color which usually warns of chili heat, but the spices were well balanced. And the reason that I have no picture of the dish is that the boys wolfed it down before I could get my phone out. Considering they’re remarkably resistant to Chinese food, even after nearly three years here, it speaks volumes about the quality of the noodles.

There’s a real art, I learned, to working with the high gluten flour needed and preventing the biangbiangmian becoming tough or rubbery. For me it was a pleasant surprise to find in our neighborhood such a distinctive example of regional cuisine, lurking in an apparently undistinguished setting.

Photo: Gary Soup via Wikimedia Commons