Since Labor Day holiday came to an end, the capital has once again been bestowed with blissfully blue skies. But this time, many Beijingers are hedging their optimism, because their hopes for a higher standard of breathing were so harshly dashed throughout much of the spring season. Yes, it’s certainly been a dispiriting but also strange period in the capital. That’s because we normally endure a heavily polluted winter, as coal refineries belch out fumes in an effort to heat the city’s millions of homes, only to be gifted with better air quality to complement fairer spring weather. And yet, the opposite has been true so far through much of 2018.

Indeed Ma Jun, who is often referred to in the news as China’s “foremost environmentalist” says: “Beijing enjoyed extremely good air quality in January and February. In fact, we were among the top 10 cleanest cities in China during that period, which is highly unusual when heating measures are is typically turned up so high.”

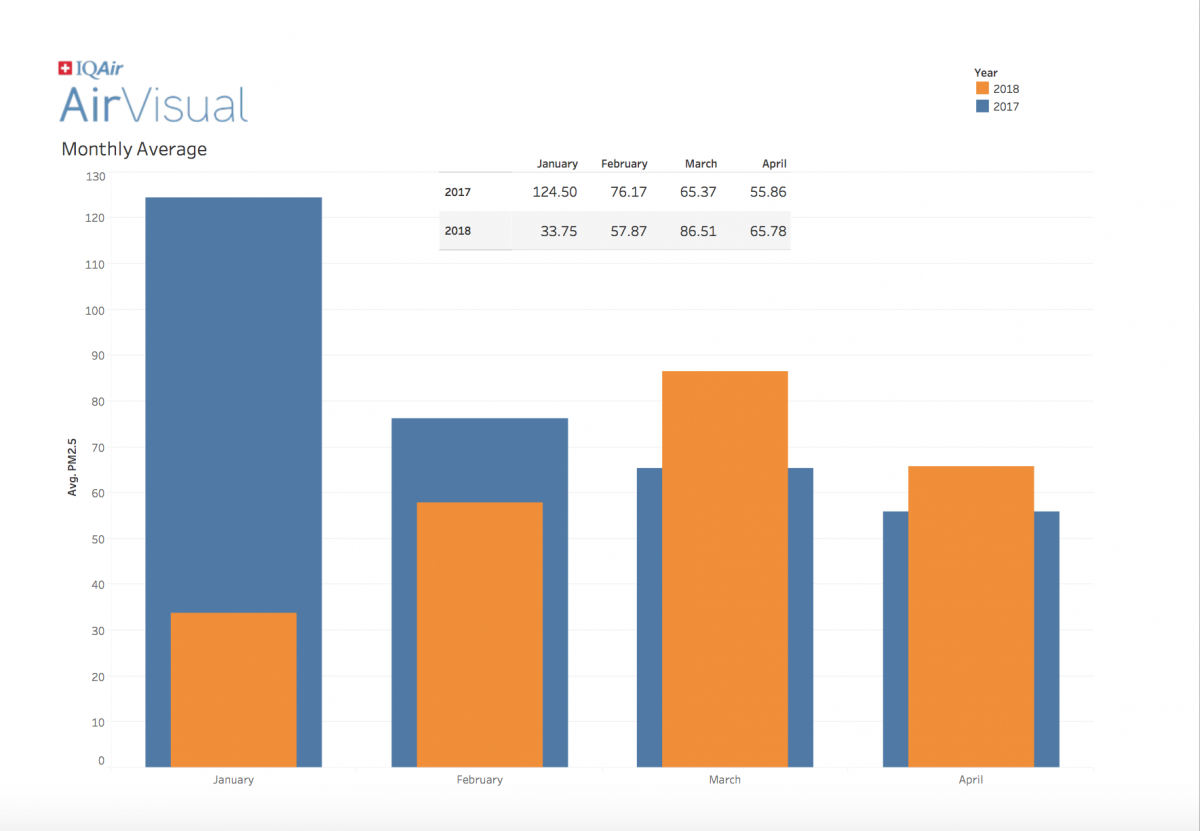

Meanwhile, Yann Boquillod, director of air quality monitoring at IQAir China (and best known as the founder of the AirVisual AQI monitor), broke down just how stark the contrast is between 2017 and 2018’s pollution levels. While January 2017’s average PM2.5 level was 124.50, that number plumetted to 33.75 during the same month this year. The difference for February was less, but still noticable, at 76.17 last year compared to 57.87 this year. Then came the switch: March of 2018 saw a PM2.5 average of 86.51, which was quite a bit higher than March 2017’s 65.37 average. April 2018, meanwhile, had a 65.78 average, compared to April 2017’s 55.86.

While March and April’s gray skies were likely left many of us feeling gloomy, the reasons behind that smog’s return should be enough to raise many a Beijingers’ ire.

Wei Huang, a climate and energy expert at Greenpeace, attributes January and February’s improved conditions to the most recent official five-year plan implemented by China’s Ministry of Environment. Among its targets: reducing the concentration of PM2.5 in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region by 25 percent by 2017, and ensuring the annual concentration in Beijing does not exceed 60 micrograms per cubic meter. Wei says the capital was short of that goal throughout much of 2017, prompting a ramp-up in early 2018 that lead to crisp, clear skies. She says those ends were reached through restrictions like a 50 percent decrease of emissions slapped on steel refineries in neighboring Hebei and Shandong, along with a push for electric and natural gas heating over coal.

Effective as those efforts appeared to be in early 2018, Wei says the authorities were then struck by a deeply formiddable hurdle: government bureaucracy.

“That five-year plan only covered this year’s ‘heating season,’ a term that the authorities used to refer to the winter time because of all the coal that is typically burned,” Wei says, adding. “Now that that plan is finished, we are in a gap of policy.”

In place of such a seemingly logical contingency, Wei says that during this past spring’s Two Sessions, the Ministry of Environment instead announced that it must review the results of the last five-year anti-pollution plan before taking the next step. Though Wei says it would be difficult to speculate how that will unfold, she points to a mid-way review in the five-year plan that began in 2015 and took six months to complete. While she readily understands that most Beijingers would hope the current review will be more speedy, she says: “I very much expect that they will need to carry out this review, and then begin a new plan spanning several years based on their findings.”

“Now that there are no longer restrictions on industry emissions, they can operate at any rate they want,” Wei says of the current policy lag. She went on to cite findings that one of her Greenpeace colleagues Tweeted in late March about the emission levels at steel refineries in Tangshan, a city in Hebei that is frequently referred to as one of the smoggiest cities, if not the smoggiest city in China. The operating rates in that locale before last winter’s restrictions were 85 percent. They then dropped to 50 percent thanks to more rigid policy. Wei says, “Once those measures were lifted, because of the current policy gap, their operating rates went back to 75 percent. While those are the only figures we have there for now, we have every reason to believe that the same has happened with other steel hubs, and cement and glass factories.”

Startling as those bureaucratic hiccups may be, another factor may be all the more troubling given that it’s beyond human control. That’s because favorable weather conditions were also a key aspect of Beijing’s air quality boon in early 2018, as Ma Jun points out.

“Every few days there was a cold front, and the northern winds helped to keep the dust from settling in the southern part of the city, which cleaned up the smog in Beijing,” Ma explains.

Wei concurs, adding: “The direction is important because the industries are all clustered around southeast Hebei and Shandong. So the direction of where the wind blows is a big factor as to why the AQI levels can differ so much.” However, this explanation runs counter to that of an expert, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, following the sandstorm that coated the city haze in late March, who said at the time, “The [recent]good weather was not the reason for low pollution because the weather was nearly the same as previous years.” Though that source would not comment further, Wei, went on to cite a government study that concludes roughly 20-30 percent of pollution reduction is due to favorable weather, while 70-80 percent can be chalked up to human efforts.

Both Ma and Wei conclude that when the winds shifted in March – from northern cold fronts to weaker, southern gusts – Beijing’s plumes of smog sluggishly lingered about, leaving the skies gray throughout much of the early spring.

Despite all that, Wei sees these developments as a setback rather than a cause for despair. She is heartened by China’s increased investment in renewable energy, along with improvements in the inefficiencies of green power sources, citing one study that found that those curtailments have dropped from 40 percent to 20 percent in turbine hubs like Gansu and Xinjiang over the past two years. Most of all, she points to stricter enforcement of factory restrictions this past year as a milestone in China’s ongoing slog against smog.

“Inspections determined that 80 percent of factories had some sort of violation of the rules, and [how they were dealt with]was a lot different from what happened in China in the past – they actually followed through and came back for second and third rounds of inspections to make sure that the problems had been solved,” Wei says, before adding: “The pollution coming from scattered, small factories have been detrimental to the environment as they are hard to monitor. The inspections have found that 60-80 percent of the small factories are violating environmental rules or regulations. Secondly, they now hold local officials accountable for problems that are not solved, providing a bottom-up incentive for local governments to tackle environmental problems, which could be a valuable test for a longer-term mechanism.”

Perhaps knowing that such a precedent has finally been set will provide some solace to us Beijingers having endured an extra smoggy spring, at least until the new policies finally kick in. As Wei puts it: “It looks like local officials are being held more accountable and it feels like the first time that the central government is putting environmental protection on par with economic development, and this is a very optimistic sign.”

More stories by this author here.

Email: kylemullin@truerun.com

Twitter: @MulKyle

Instagram: mullin.kyle

Photos: USA Today, IQ Air/Air Visual, Kyle Mullin