With all eyes on Amy, her mind is no longer on volleyball.

It’s her serve and judgment is all around, from the spectators in the bleachers to her uncompromising teammates on the court. In a tense moment like this one, where winning or losing the match hinges on her next move, Amy says she is most anxious when trying to beat her toughest opponent—herself.

“I need to do everything perfectly,” the Australian student tells beijingkids. “The whole process starts with me putting pressure on myself, which then makes me nervous, which then starts to affect my overall performance.”

Amy (not her actual name) is one of Beijing’s thousands of foreign students grappling with the anxiety that comes with adapting to a new life in another country. By nature, international schools are transient communities; students and teachers come and go all the time. Goodbyes become harder, and stress can easily become contagious, widespread, and inescapable. That’s why many of the city’s international schools are now devoting a larger part of their curriculums to easing the stress of these major transitions, reworking and refining their mental health support systems to offer more comprehensive counseling services and mindfulness training.

When Amy’s anxiety began to interfere with her life off the volleyball court, she and her parents agreed it was time to meet with a counselor. They worked together, in what became a comfortable, confidential environment, mapping out ways to help Amy confront and treat her unease. Those strategies included sharpening her social skills, and working on how best to resolve conflict with her teammates. But this sort of help doesn’t quite work if parental involvement is lax. Without that familiar encouragement, a child is less likely to approach, much less trust, an advisor or counselor they barely know.

“It’s got to be a collaborative team approach,” said Jane Farrelly, who leads the Child Protection Team at Beijing City International School (BCIS), one of the schools offering mental health support. “It’s unrealistic to think that only four counselors are going to service the kids—it’s impossible.”

Since BCIS was founded in 2005, its preventative model of addressing mental health has demanded that teachers, advisors, and counselors engage constantly with their students in order to build and nurture trust—get to know them before conflicts arise. “The best work happens when a whole community is focused on something together,” said Tori McClanahan, the advisory coordinator for the secondary school, Grades 6 to 12.

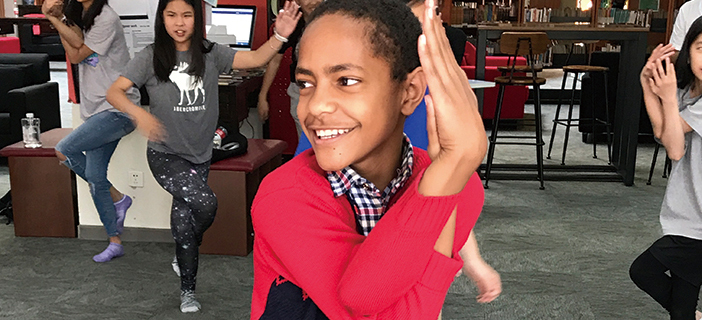

At BCIS, establishing that initial trust begins with travel. The secondary school hosts trips known as Week Without Walls, to places outside of Beijing, adventures that are meant to spark those long-lasting student-teacher relationships, inspire self-confidence, and encourage resilience in the face of stress. This year, BCIS also expanded its Wellness Day program, which incorporates mindfulness training including yoga and lessons on proper breathing and self-control during heightened moments of anger or anxiety.

Recognizing signs of stress in students is nearly impossible if no trust exists between them and their teachers. Regular checking in can make students feel comfortable enough to open up and approach someone. But that’s only one step. The teacher might then pursue a bit further, and work to identify students in need who aren’t showing obvious signs of stress, anxiety, trauma, or depression. Why? Often, students are so good at burying their feelings that they “become invisible,” Farrelly warned. “Adolescents are not naturally help-seekers. That’s why if we can talk about things that are uncomfortable to a wider group, it helps break down stigma. It’s only through having those conversations that you build understanding.”

Those conversations are expanding at Beijing’s international schools at a crucial time in China, where many still consider mental illness shameful, if they acknowledge it at all. Some locals continue to fear and even avoid relatives and friends struggling with anxiety or depression, lest they lose face. Weekly therapy appointments might be the norm back in the West, but here in China 92 percent of those diagnosed with mental disorders never seek help. There’s the soaring cost of treatment, which insurance plans here do not cover. Also, few doctors practice outside of the big cities like Beijing, leaving many rural areas without psychiatric facilities. But perhaps most telling is the country’s persistent, negative view of mental illness, which has been fading in recent years, if only gradually.

A complicated history points to why. Until Mao founded the People’s Republic of China in 1949, not one psychiatric hospital existed in the country. And here in Beijing, mental health services were not available until 1958. It would take several generations for the government to produce its most demanding and sweeping reforms, when China’s first mental health law went into effect in 2013.

“For the older generation, they didn’t really receive a lot of mental health education,” said Dilys Liu, an elementary school counselor at Western Academy of Beijing (WAB). “In mainland China, we still have a lack of professionally trained therapists and psychologists.”

Those limitations won’t help bring down the expensive cost of therapy appointments and other mental-health treatment. Because many foreigners living in Beijing can’t afford the kind of one-on-one help private providers offer, these international school services are a perk, even a reward, at the other end of that stressful transition that first brought them here. WAB’s high school even offers its teachers access to a network listing the name of every international school counselor in Beijing, yet another invaluable resource for finding providers when clinic visits are out of the question.

“We encourage the teachers and parents to seek help,” said Liu, who is in her first year working at WAB. “We try to set a good model for the students to say, ‘It’s O.K.; we do feel upset sometimes, and we can always seek help.’” WAB goes so far as to bring in occupational therapists and psychotherapists once a week as part of the services it offers teachers.

“I was lucky enough to find a bilingual therapist to sit down with to talk about the transition shock, the culture shock,” said one international school teacher from the U.S., who also manages a mindfulness-based community group on WeChat. “Mental health awareness is not a widely welcomed or appreciated idea. The idea is embryonic right now, and with 20 million people in one city, it’s that much more necessary.”

Now more than ever, teachers at schools like BCIS and WAB are encouraged to strengthen their own mental health and wellbeing, while also guiding their students. “We want to make sure that our educators feel empowered,” said McClanahan, “and have the mental, physical, and emotional supports that make us well-rounded and happy people.” Some of those teachers have gotten creatively ambitious: earlier this year, after forming a workplace-wellness committee, 30 of them decided to train for a triathlon.

While there is no specific age when a child first decides to approach someone for help, Liu says WAB emphasizes early intervention with its youngest students. Early intervention means kids will likely take initiative later; some as young as six years have proactively sought time with a counselor at WAB.

Before joining the elementary school this year as a counselor, Liu worked as a psychotherapist at New Century International Children’s Hospital. Today, she sometimes incorporates play therapy into her teaching, an exercise that empowers children to physically work through emotions they can’t yet express emotionally.

WAB recgonizes three different stages of their students’ lives, each with its own challenges: early development (ages 3 to 5), who often are beginning to show attention-related and behavioral issues; ages 6 to 11, who are starting to show signs of anxiety and are experiencing conflict, sometimes with friends; and ages 12 to 17, who might be suffering from stress related to deeper problems at home, including parental separation or divorce.

Across the board, counselors at Beijing’s international schools encourage students to discuss their most sensitive family issues, recognize and address their impulses, and work through smartphone addiction and negative body-image perception.

“To have foreign kids adapt to a new climate, culture, and far-away society is a challenge,” said a teacher from Russia, who also counsels middle- and high-school students with special needs. “But in the end, it’s all about learning.”

Stapled to a bright wall in the hallway outside Jane Farrelly’s office at BCIS are typed personal reflections, a couple of lines students wrote based on their experiences with counselors: “I always thought sharing your personal feelings would make someone look weak, when it’s actually a good skill,” one reads. Another goes a bit deeper: “Talk to parents and friends about your feelings, whether it’s sad or angry. Stereotype is bad. Do not judge anyone.”

One of BCIS’s more intriguing approaches to addressing sensitive issues with young students is its “one-step-removed process.” The approach advocates for trust and disclosure while employing a somewhat indirect technique of intervention. For example: To softly address the painful, sometimes unspeakable issue of abuse, a student might be shown a few unsettling minutes of the film “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.” This way, rather than abruptly address abuse with too many questions face-to-face, the movie clip is known to help students navigate tough conversations without feeling the pressure to reveal too much about the most sensitive struggle of their lives.

In 2014, more than 4 million people living in China were classified by the government as severely mentally ill—with fewer than two psychiatrists for every 100,000 people, according to The Economist. As an indicator of how far we’ve come, consider this: Beijing’s first private mental health clinic didn’t open until three years ago.

Today, as the world’s largest country approaches its 70th year of Communist leadership, China’s National Mental Health Work Plan has called for an overhaul of its “inadequate and unevenly distributed” mental health services by 2020—specifically within every school. For years, many of Beijing’s international schools have been well ahead of the curve, offering mental health services in a part of the world that has long considered them taboo.

“With so many cultures and different backgrounds, there’s a fairly big need for support,” said Amy, who continues to work through her sports anxiety. “Our school counselors really do try to go out there, find students that need help, and make sure they know that it’s a safe community. That’s really comforting.”

This post appeared on the beijingkids October 2018 Mental Health issue.

Photos: Courtesy of BCIS and WAB