Some eyebrows were raised in the world of education when STEM – a program to promote the study of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Maths – became STEAM. Many feared that the addition of Arts to the program would water it down, taking the focus away from the harder subjects which will be essential to kids in the 21st century. But Beijing teacher and entrepreneur Alex Ibrahim is in no doubt of the value of encouraging kids to be creative.

“The best way to teach kids is to make it fun,” he told us, “and make sure they have their hands on. They absorb things deeper if they do it themselves. Crafts also help kids to be themselves: the colors they choose, the way they do their projects, how they put things together, all of these tiny details are just small steps in their growing-up experience. And they can help teachers to understand their students better.”

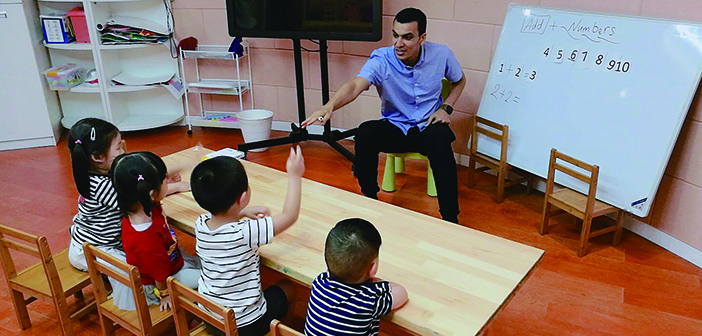

Ibrahim brings his innovative approach to learning to kindergartens in Beijing and beyond, using craft activities as a way of teaching not only STEAM but language too. And it was language study which first brought him to China.

“I was planning to stay for a year or two,” he said, “but I found out that my Chinese was not that good, so I decided to stay one more year, get my Mandarin right. I was a teacher before I came to China, so I did some part-time teaching while I was a student. I did that for two years, in small training centers and one-on-one programs. I saved some money, and started a training center of my own. I found that I was using tons of books, so I developed my own materials, and started to sell them to kindergartens.”

“I was planning to stay for a year or two,” he said, “but I found out that my Chinese was not that good, so I decided to stay one more year, get my Mandarin right. I was a teacher before I came to China, so I did some part-time teaching while I was a student. I did that for two years, in small training centers and one-on-one programs. I saved some money, and started a training center of my own. I found that I was using tons of books, so I developed my own materials, and started to sell them to kindergartens.”

But a key element was missing.

“My classes were out of control, a little bit boring,” Ibrahim said, “so I thought something was wrong. I took some online courses, and got advice from friends. As a result I started using art, and it went so well, I now do it in every single class.”

The purpose of the craft activity is not just to teach English as a language, but western culture too.

“The classes have themes. We start with the seasons, which gives us the chance to do science experiments. When we get to summer, we talk about going to the beach. Then we bring in arts and crafts, so we make a towel, and a beachball, or an umbrella. Usually each theme takes a week, but the kids are pretty young, so we take it slowly. I also train other teachers, on how to prepare lessons and manage a class.”

Kids absorb things deeper if they do it themselves

Now Ibrahim has taken his program into cyberspace, with a series on video-sharing platform iQiyi, called Craft 젬촉 (lián méng), “Craft Club”. Each lively ten-minute show has Ibrahim demonstrating a craft activity suitable for young children, in fluent Mandarin.

“The activities use very simple materials you can easily buy online,” he said, “and introduces just one or two English words. We’ve filmed 18 so far, and we’re doing 30 in total. We’ll know how it’s gone by the end of November, but so far so good.”

“The activities use very simple materials you can easily buy online,” he said, “and introduces just one or two English words. We’ve filmed 18 so far, and we’re doing 30 in total. We’ll know how it’s gone by the end of November, but so far so good.”

Ibrahim is very aware of the need to bring opportunities to children beyond the Tier One cities.

“Something I’m planning to do each year, is for four to six weeks go to very poor villages and smaller cities, to stay there and teach the kids, culture, science, and English. These are places where they don’t have many chances to see foreign faces. There’s a village in Hunan I’m planning to go to this winter, and an orphanage here in Beijing, where I’m going to do charity things with kids, like parties for Halloween and Thanksgiving.”

Ibrahim has also taught in the US and Turkey, and his experience emphasizes the importance of letting children do things for themselves.

“In the west kids are more willing to listen. In China, some kids just wait for you to do things for them, and cry to get what they want. It’s down to how the parents and grandparents deal with them. But it’s only two or three out of every ten. Overall they’re very good.”

As he told us though, letting young children get hands on with paint can sometimes be a messy experience.

“There was one kid who, every time I wore a white shirt, would eat with his fingers and then put his hand on my shirt. One day we were doing finger painting, but he decided to use his whole hand. I was helping another student, when I felt a hand on my back… The kid loved me, so I wasn’t angry. I said, ‘Do another one on the front!’ I thought I could clean it off, but I couldn’t, so I lost my shirt. But it was so much fun.”

This article appeared in the beijingkids November 2018 Beijing Makers issue

Photos: Courtesy of Alex Ibrahim