Warning: This article contains references to self-harm. Links lead to pictures which may distress young children.

In 2017, we reported in depth on the “Blue Whale suicide game“, which had spread around the world from its origins in Russia and arrived in China. We found that the “game” did not really exist, but that well-meaning warnings were actually responsible for spreading the idea, which proved a magnet to troubled young people. (It’s a testament to the idea’s persistence that we still continue to receive comments on the article asking for links to the game. After the first, we have not published or responded to these comments.)

Now another scare story is making the rounds of social media, and it’s a familiar one. A game (or video, or evil spirit – the details vary) has become a craze among young people, in which they are dared to undertake dangerous or self-harming challenges, culminating in their suicide. The story is accompanied by disturbing but unsubstantiated reports about the number of deaths caused, and (as with Blue Whale) a BBC report is often cited to give credence to the claims.

The story is also accompanied by a disturbing picture of a frightening, doll-like face, said to be Momo. In fact, as revealed by thatsnonsense.com, the picture is of a sculpture called “Mother Bird” created by a Japanese special effects studio and posted by them on Instagram. We have taken the decision not to use this picture, as it may upset young children – and because sharing it is making the problem worse.

It’s obvious that “Momo” is the Blue Whale having mutated, as viral ideas do when their older forms become less effective. There is no “Momo Challenge”, and “she” certainly has not infiltrated children’s cartoons like Peppa Pig on Youtube (although it’s only a matter of time before this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, and a prankster creates just such a video.) Well-meaning attempts to keep children safe by warning parents are in fact mainly responsible for spreading the story, which then makes it available to young people who are already distressed and at risk of self-harm.

We urge you not to share any stories about “the Momo Challenge” on social media, and to encourage others to do likewise. Warnings such as these actually put children at risk. As ever, the best way to keep our children safe is to take an interest in their lives, keep communication open, and not to allow unsupervised access to the Internet until you are confident they are mature enough to cope with the many dangers online.

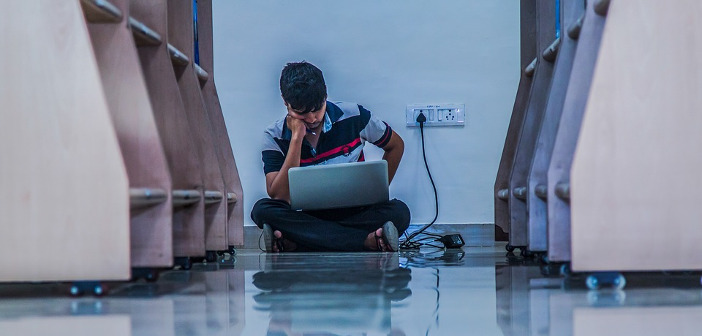

Photo: Pixabay