Friends remark that Kenya has all the grace and quaint charm of 40s London. This is in no small part due to our British colonial legacy. From our flat vowel pronunciation to our attitude towards “polite society”, the legacy of colonialism in Kenya has permanently woven itself into the country’s cultural fabric. It somewhat boggles the mind to realize that Christianity and its accompanying traditions did not truly reach the heart of East Africa until a little more than 120 years ago. And as the faith and culture of the British spread and coalesced, so too did the traditions and rituals. And as they spread inward, many of these traditions took distinctively native characteristics. In a country as large and as diverse as Kenya, no one would ever expect a uniform Christmas tradition.

There is, however, a specially accepted Kenyan Christmas despite there being over 42 tribes and numerous religious beliefs within the Kenyan borders. It is a simple formula which ensures success and basically goes like this – roast goat, chicken stew, rice, chapatti, and some version of mashed potato. The meat of choice might vary, from fish in the West Lake Victoria area, to camel towards the north-east of the country.

For me, the idea of Christmas being just a one or two day affair is entirely foreign. Even as an adult, I still consider the beginning of December as the beginning of Christmas proper. As a primary school pupil, it marked the start of the longest school holiday of the year. December was the month of plenty: plenty of eating, plenty of relatives, and plenty of heat.

December also meant mandatory visits with relatives upcountry. Children all over the city would be swiftly shipped out as fast as our parents could manage it. I was always all too happy to be bundled up and sent to my grandmother’s farm. The great exile meant I would also get to see cousins I would otherwise never get to see in the year. I would also get to flex my linguistic muscles as I regaled relatives with my exploits in the city in my then-broken Kikuyu – my mother’s tribal language.

The mango, macadamia nut, and avocado trees would be in full bloom. Mornings would be spent browsing for ripe fruit or fallen nuts. We city kids would especially be excited about the prospect of learning how to milk the cows. So, while my aunt Monica was busy doing the milking, we would all gather around her with our little cup ready to tackle the task, learning how to roll, squeeze, and pull on the pink fleshy teat of an otherwise impatient cow.

My grandmother owned a modest coffee farm. Every once in a while we would be expected to help with coffee picking. I learned, to my great delight, that the red coffee berries ripe for the picking were also bursting with syrup. I got into the habit of sucking on the berries, until I later learned that where there is syrup, there might also be worms. It was not only a time of great adventure, but also one of barefooted bliss. I would get to walk around letting the richness of the red volcanic soil seep into my skin and stain my feet.

One day, however, stood out the most in all the excitement and festivity of the season: Christmas day. The notion of Santa was a quaint ‘white people’ idea to us. Suffice it to say we neither believed in nor cared much about him. Christmas Eve held no magic. It was just the day standing between us and the festivities to come.

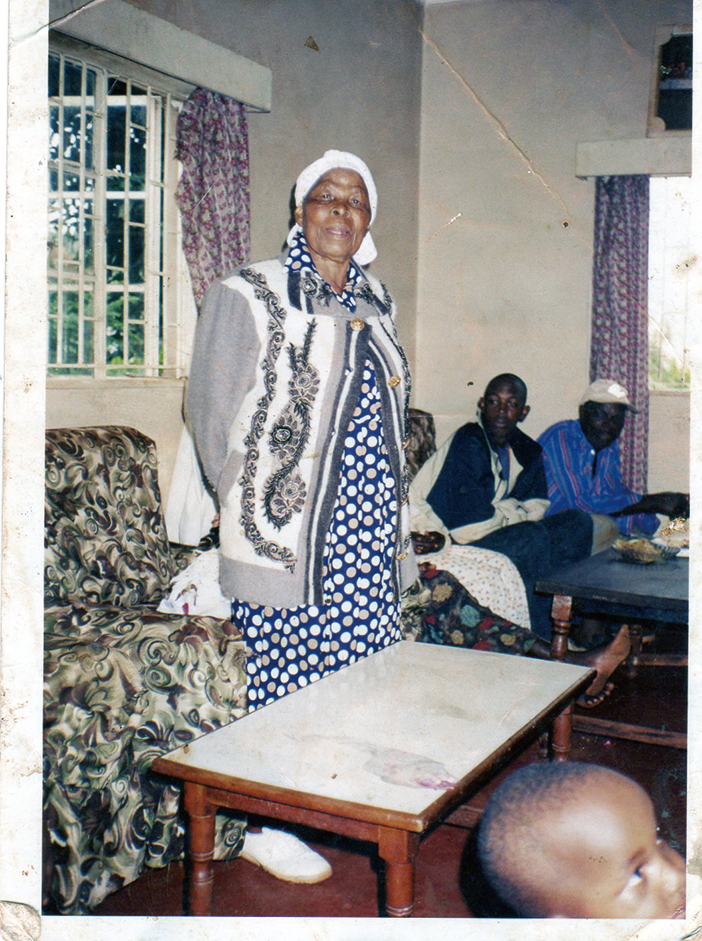

In my family, as in most others, the Christmas church service was a part of the ritual celebrations not to be dispensed with. Mine was a family of staunch Christians, none more so than my grandmother who demanded strict attendance to the Christmas church service. It is quite a big ask for a child to sit attentively through a two-hour church service. But I loved the hymns and carols sung in Kikuyu. It was there I would get reacquainted with all the neighboring families in the village. These were families who had known ours for many years. It was always in a congregation of jolly old ladies that I would be reintroduced, and they would offer up guesses as to whose child I was. Was I Dorcas’ boy perhaps? No, her children are much older. No, I surely must be Damaris’ boy. The resemblance is uncanny. It was after this joyous discovery that these old ladies would often gift me with money for sweets, which would promptly be spent on the way home.

In my family, as in most others, the Christmas church service was a part of the ritual celebrations not to be dispensed with. Mine was a family of staunch Christians, none more so than my grandmother who demanded strict attendance to the Christmas church service. It is quite a big ask for a child to sit attentively through a two-hour church service. But I loved the hymns and carols sung in Kikuyu. It was there I would get reacquainted with all the neighboring families in the village. These were families who had known ours for many years. It was always in a congregation of jolly old ladies that I would be reintroduced, and they would offer up guesses as to whose child I was. Was I Dorcas’ boy perhaps? No, her children are much older. No, I surely must be Damaris’ boy. The resemblance is uncanny. It was after this joyous discovery that these old ladies would often gift me with money for sweets, which would promptly be spent on the way home.

Santa never visited my home and I would wager he never visited my friends’ homes either. We all knew what we were getting for Christmas long before the day itself: new clothes and shoes. This is when we would grow our inventories of Sunday-best outfits. In a country where we were all expected to wear uniforms to school, Christmas clothes presented a welcome reprieve. On Christmas morning, we would excitedly try on our outfits. The trick however was to buy the outfit two or three sizes too big. The clothes were not just for the one day, but the year as well. Parents would buy them with rapidly growing bodies in mind, and how to get the most out of what would often be expensive little outfits. What was hard on the day however was trying to keep the outfits clean. I learned very quickly that red volcanic soil wasn’t compatible with new Christmas clothes, and neither was roughhousing with my cousins.

If there was one thing that made the church service all the more unbearable, it was the anticipation of the food to follow. What was to be had varied yearly, determined by variables such as family members expected, whether or not there would be a baptism, or even whether one of the cousins had undergone initiation that December. But that’s a whole other story.

Part of the food festivities would involve some sort of slaughter.

On slower Christmases, a rooster or two would have to do. On grander occasions a goat would bite the dust, but on especially festive years, it would be a bull.

On slower Christmases, a rooster or two would have to do. On grander occasions a goat would bite the dust, but on especially festive years, it would be a bull.

The bull or goat slaughter would be left to my uncles and the older sons of the family. It followed slaughter traditions passed down for generations, by tying the animal down and laying it on a bed of freshly cut banana leaves. Decapitation of the animal would then be achieved with great precision by the uncle with the most experience. It was done over a pot or pan to collect the draining blood, which would later be used in the making of blood sausage made from the animal’s large intestines stuffed with odd cuts called Mutura.

It was never an activity for the squeamish. But none of us were. We all grew up watching our uncles and older cousins perform the slaughter, carefully roast the meat over a pit of coal, and lovingly apportion it appropriately to the different homesteads in the family compound. This was done depending upon the ages of the children in the home, the number of guests visiting each individual household, and obviously how big the bull or goat slaughtered was. Some of the more succulent cuts would be saved for my grandmother and more mature aunts and uncles.

Roast goat or beef was however meant to be the pièce de résistance to a grander feast of choice delights. For example, back then, a Kenyan favorite – chapatti – was often saved for special occasions. Christmas without chapatti was like a pub without beer – unimaginable. My people are big fans of a bean, pumpkin leaf, and potato mash which is called Mukimo – a “mashed mixture”. Kitchen duties would often be a collaborative affair with each aunt or cousin watching over a pot or two, feeding the fire, or kneading the dough. Some of the cuts from the slaughter would always make their way to the stew. There was always pilau. Bean, pea or vegetable stew and panfried greens – mostly a mixture of kale and spinach – were all mainstays at Christmas.

Now, it might be customary in other countries, indeed even other households, to have a Christmas tipple after the day’s festivities and grand meal. But that would never fly in my grandmother’s house. She believed that a day’s hard work could only be complimented by a warming mug of fresh milk tea. Liters of the stuff would be brewed and kept warm in large colorful flasks won in raffles, and one after the other, we were expected to have at least a cup. Being a city kid, I had other inclinations. Soda mostly, which was never there in plenty or on demand as it would have had I been at home.

But this too gave the otherwise mundane act of drinking a Fanta an almost magical potency even for a city kid. The adults would all gift us with a little money, which we would take straight to the shops and spend on single-sold balloons, sodas or fried dough called ngumu, which in literal terms means hard, as the dough bits would be fried to an unyielding, hard, golden brown crisp.

And if the festivities fell on a Saturday, then we would all be in for a treat, as we would get to watch WWE wrestling – then known as WWF – on my grandmother’s tiny black and white television, powered by a car battery, in lieu of electricity.

For me, however, it was never so much about the food as much as it was not being a city kid for a month or so. Christmas for me represented an abandonment of the ordinary and a definite shift into freedom and the making of wonderful childhood memories. It was a ritual which would begin with saying goodbye to my friends on closing day, weeks before the day itself, the taking of several matatu – buses and public taxis – from the city to my grandmother’s farm, and finally being greeted by the absolute tranquility of simple country life. Christmas was not just one day for me or my friends. Coming from a country as big as Kenya, we all had our own special rituals, some similar and some wildly different from each other. One thing was for certain, however: on opening day and for weeks to come, we would be reliving the memories created with our friends, and again relive the wonder of Christmas.

For me, however, it was never so much about the food as much as it was not being a city kid for a month or so. Christmas for me represented an abandonment of the ordinary and a definite shift into freedom and the making of wonderful childhood memories. It was a ritual which would begin with saying goodbye to my friends on closing day, weeks before the day itself, the taking of several matatu – buses and public taxis – from the city to my grandmother’s farm, and finally being greeted by the absolute tranquility of simple country life. Christmas was not just one day for me or my friends. Coming from a country as big as Kenya, we all had our own special rituals, some similar and some wildly different from each other. One thing was for certain, however: on opening day and for weeks to come, we would be reliving the memories created with our friends, and again relive the wonder of Christmas.

Photos: Mark Karanja

This article appeared in the beijingkids December 2019 Giving Back issue

This article appeared in the beijingkids December 2019 Giving Back issue