The issue of water scarcity in Beijing is often ignored. We all think that Beijing, being a megacity, surely cannot be experiencing water scarcity! However, water scarcity is indeed present in Beijing, and this overlooked problem has placed an increasing burden on the government.

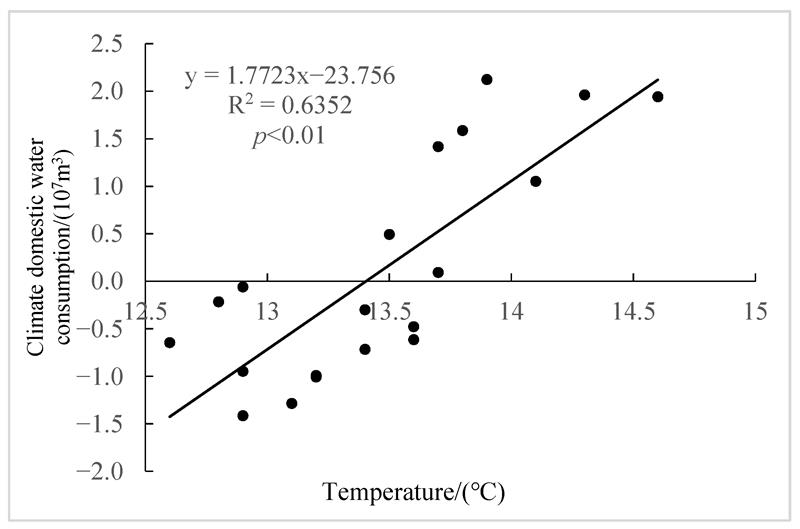

One of the biggest causes of water scarcity is climate change. A study published in 2022 titled “Response of Domestic Water in Beijing to Climate Change” found an increase in climate change caused an increase in domestic water consumption. Using historical meteorological data and domestic water use data, they found that the relationship between annual domestic water consumption and climate change in Beijing was 177.23 million m³/°C (shown in Figure 1). This means that for every one degree increase in Beijing’s average temperature, Beijing’s annual domestic water consumption increases by 177.23 million m³ of water.

On average, every person’s water consumption increases by 8.1 m³ of water per year. To put that into context, 8.1 m³ is the size of 27 300L bathtubs or 16,200 500mL water bottles. It is important to note that this is only for domestic water consumption: it does not take into account industrial water consumption. This means that the effect of climate change on total water consumption in Beijing is even greater.

On average, every person’s water consumption increases by 8.1 m³ of water per year. To put that into context, 8.1 m³ is the size of 27 300L bathtubs or 16,200 500mL water bottles. It is important to note that this is only for domestic water consumption: it does not take into account industrial water consumption. This means that the effect of climate change on total water consumption in Beijing is even greater.

Figure 1: The relationship between climate domestic water consumption and temperature

Not only does climate change affect water consumption, but it also affects the availability of freshwater. With the average global temperature rising by around 3.5 degrees in the past century, 82 percent of China’s glaciers have retreated since the 1950s, which means a fifth of the ice cover has disappeared since the 1950s.

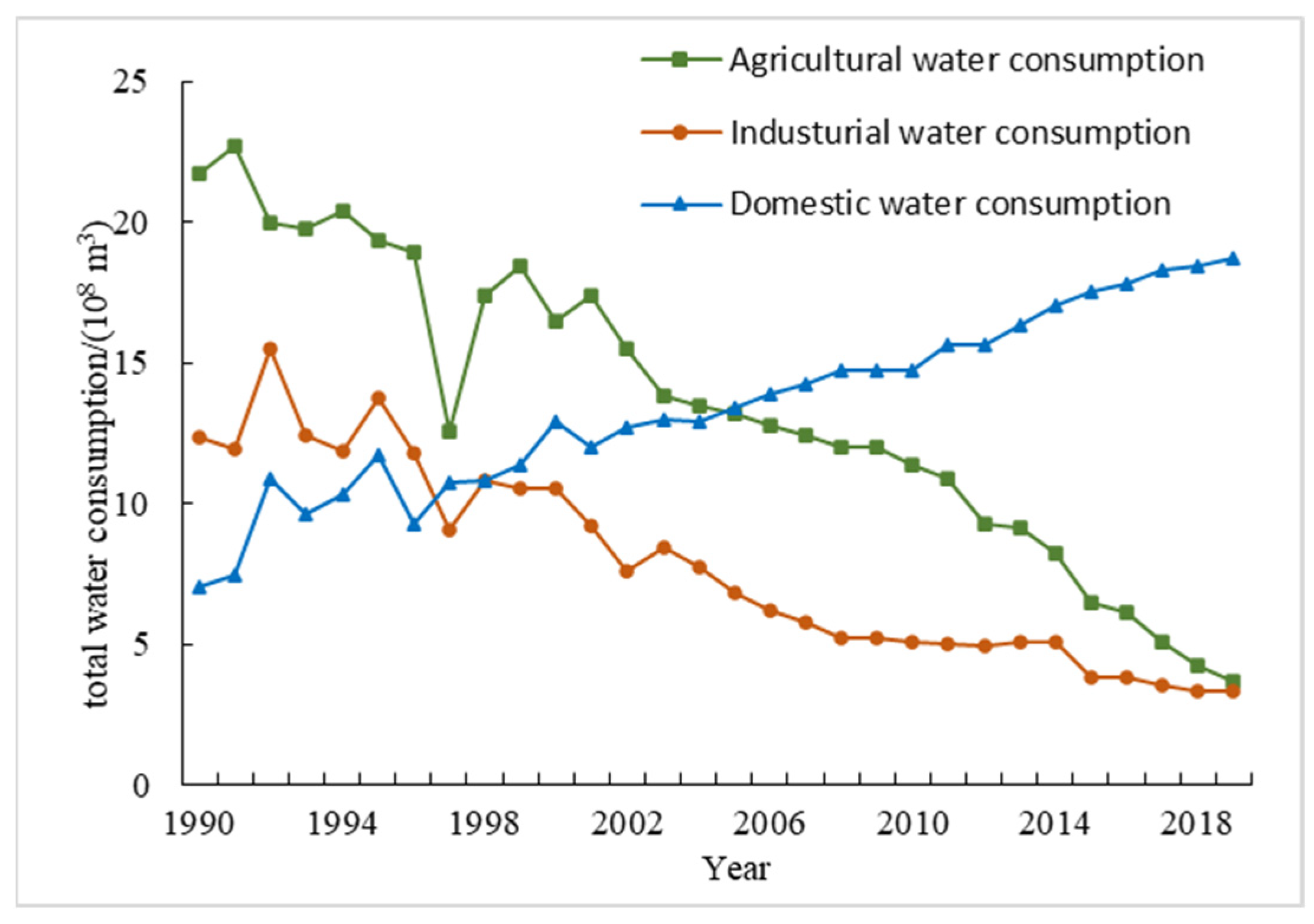

So, what’s the greatest consumption of water in China? Overall, agriculture takes up 67 percent of total water withdrawal in China. However, in recent years, domestic water use has risen to become the number one usage of water in Beijing, which makes domestic water use a significant cause of water scarcity.

Figure 2: Total water consumption in different sectors

The consequences of water consumption are widespread. In 2014 there was on average 145 m³ of renewable freshwater available per person in Beijing. This might seem like a lot, but according to the UN “When annual water supplies drop below 1,000 m³ per person, the population faces water scarcity, and below 500 cubic metres ‘absolute scarcity’.” The depletion of water sources has caused the Chaoyang zone to sink by 4.3 inches (around 11cm), even though 70 percent of water is already coming from the South-to-North water diversion project.

Water from other provinces is incredibly expensive and will be even more so in the future. The South-to-North water diversion project has cost China USD 60 billion to construct. Based on the predictions from the trend relating to climate change and domestic water consumption, the additional cost to transport water from other provinces to Beijing in 2035 compared to 2019 could amount to CNY 391-706 million!

One solution that has already been implemented is the South-to-North water diversion project. It links China’s four main rivers (the Yellow River, the Huaihe River, the Haihe River, and the Yangtze River) together, diverting “44.8 billion cubic meters of water annually to the population centers in northern China,” spanning a total of 4,350km, and holds records for the world’s largest water diversion volume, largest water diversion distance, largest population benefited and largest scope of benefited. Of course, some are worried that because water consumption is still on the rise, the South-to-North water diversion project is only a short-term solution. Others even believe that this only distracts from focusing on the root of the issue.

One solution that has already been implemented is the South-to-North water diversion project. It links China’s four main rivers (the Yellow River, the Huaihe River, the Haihe River, and the Yangtze River) together, diverting “44.8 billion cubic meters of water annually to the population centers in northern China,” spanning a total of 4,350km, and holds records for the world’s largest water diversion volume, largest water diversion distance, largest population benefited and largest scope of benefited. Of course, some are worried that because water consumption is still on the rise, the South-to-North water diversion project is only a short-term solution. Others even believe that this only distracts from focusing on the root of the issue.

Figure 3: Map of the South-to-North water diversion project routes.

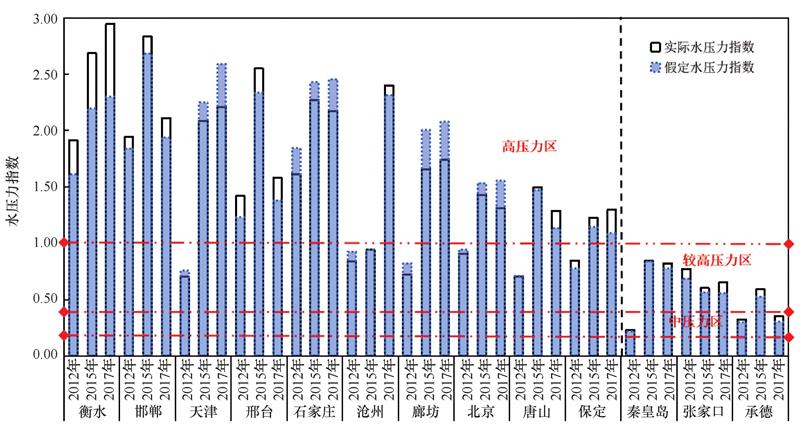

Another solution is to encourage virtual water flows. These are indirect flows of water caused by the transportation of products containing water. The water intensive activities are done in one province, and then the products are transported to another. One example is the transportation of grain. A lot of water was used to grow the grain, and after it has been harvested, it is transported to the city.

According to research: “The virtual water flow in urban agglomerations significantly alleviated the water stress in the central city, where the actual water stress index decreased by an average of 12% compared with the hypothetical water stress index after virtual water flows.” However, the side effect is that cities providing virtual water flows have an increase in water stress levels.

According to research: “The virtual water flow in urban agglomerations significantly alleviated the water stress in the central city, where the actual water stress index decreased by an average of 12% compared with the hypothetical water stress index after virtual water flows.” However, the side effect is that cities providing virtual water flows have an increase in water stress levels.

Figure 4: The actual water stress levels (shown with the black outlined boxes) compared to hypothetical water stress levels (shown with blue dotted-line boxes). Levels above 1.0 on the y-axis means water scarcity in that city is significant.

We all have our part to play in reducing water scarcity. Governments have to work on developing “science- and evidence-based policies that capitalize on data and innovation to improve water planning and management” to combat water scarcity. When planning solutions and deciding which areas need support, we must take into account the quality of water.

Because farmers already deal with water on a daily basis, they should “take [the]lead in finding and implementing water scarcity solutions.” To do so would require us to provide them with “appropriate technologies, training, and timely, accurate information.” There should also be a greater proportion of farmers participating in the planning and decision-making process.

Each and every one of us has to value water. After all, we use up the most water in the economy. The UN says we should make “informed decisions about the products we buy.” Wasting less water when cooking or washing our hands are simple everyday actions that can all add up to reducing water scarcity. You can also raise awareness on the issue. Share this article with your friends and family!

This article was written by a group of students from Yew Chung International School of Beijing (YCIS).

Terrence Yu is a Year 11 student who enjoys volleyball, music, and solving mathematical problems. He was drawn to this issue by curiosity: Why is Beijing as a megacity facing the problem of severe water scarcity? What are some causes, consequences, and solutions for it?

Jessica Zhao is a Year 11 student who enjoys playing music and doing crafts. She was drawn to this issue by curiosity: What has caused this problem? What could we do to help? What is already done and planned for the future?

Eric Zhang is a Year 11 student who enjoys playing football and reading novels. He was drawn to this issue by curiosity: Are people who live in Beijing aware that the city they are living in has the problem of water scarcity? What should different people in society do to help solve the problem?

Sum Chan is a Year 11 student who enjoys swimming, playing the guitar, and loves to learn about physics. He is very interested in the topic because he wasn’t particularly aware of the water scarcity in Beijing.

Images: Courtesy of students, Pexels