Are you as curious about who’s shaping the young minds of our kids as we are? We’re sitting down with teachers and staff from Beijing’s vibrant international schools to learn more about their unique stories, experiences, and perspectives. From the challenges of adapting to a new culture to the joys of building connections across borders, these conversations will shine a light on those who make up our education community. Whether you’re part of an international school yourself or simply curious about life in Beijing’s globalized education hubs, join us as we get to know the people behind the classrooms, hallways, and campuses that shape this extraordinary world.

This week’s #BeijingEducators features Joanne Merritt, the head of the psychology department at Dulwich College Beijing (DCB).

Originally from West Yorkshire in the UK, Merritt has been in Beijing for 11 years. She has a diverse career spanning psychology, education, and leadership in various countries. She moved from teaching psychology and sociology in mainstream comprehensive schools to a government-funded program that provided education, support and advocacy to what were called “hard to reach” children back then. Merritt wanted to use her understanding of psychology in a more practical setting, but after two years found that she missed the challenge of teaching too much. That’s when she began looking for local teaching roles again and came across the opportunity to work in Beijing and thought, “Why not?” – not really expecting much to come of it. The rest is history.

Originally from West Yorkshire in the UK, Merritt has been in Beijing for 11 years. She has a diverse career spanning psychology, education, and leadership in various countries. She moved from teaching psychology and sociology in mainstream comprehensive schools to a government-funded program that provided education, support and advocacy to what were called “hard to reach” children back then. Merritt wanted to use her understanding of psychology in a more practical setting, but after two years found that she missed the challenge of teaching too much. That’s when she began looking for local teaching roles again and came across the opportunity to work in Beijing and thought, “Why not?” – not really expecting much to come of it. The rest is history.

Let’s get to know you a bit.

Let’s get to know you a bit.

How does your background in psychology influence your approach to leadership and education?

I can’t escape it, not that I would want to! I think it helps to have a little bit of an understanding of behavior in any situation. It’s actually something I tell my students when they ask me what career paths follow from studying psychology: Tell me a job where, at some point, you won’t need to interact with yourself, people or animals? From taking an empathy-based approach with colleagues to using teaching methods informed by cognitive psychology to make knowledge “stick,” psychology is a fundamental part of my approach in everything that I do.

With your post-graduate qualifications in innovation in education, what are some key innovations or leadership philosophies you’ve incorporated into your daily work at DCB?

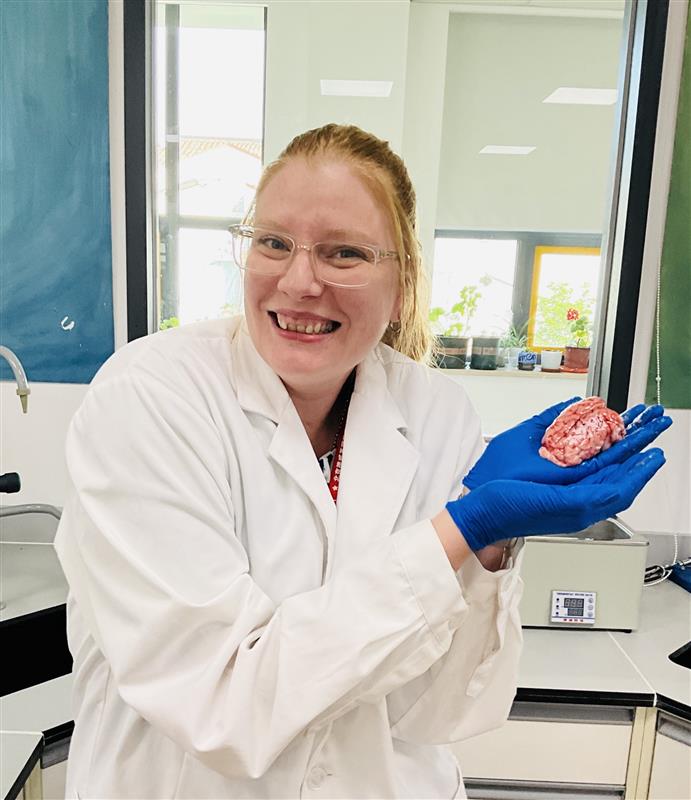

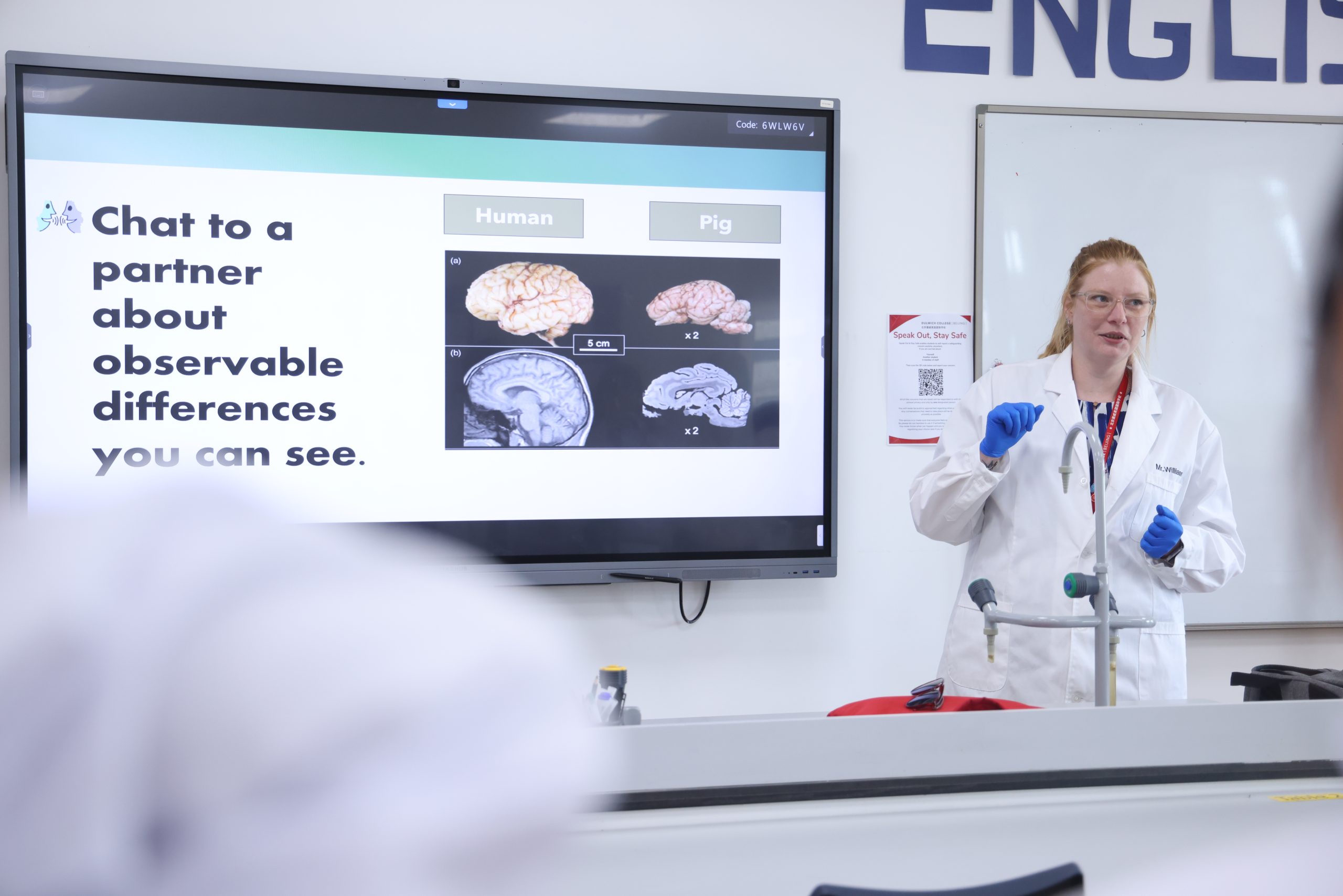

I try to incorporate something creative into each topic that I’m teaching to sustain focus and act as consolidation/stretch or a memory-enhancing experience, often without students realizing that this is taking place. So, a cheeky learning bonus, of sorts.

For example, one of my GCSE groups has just finished creating medicine packaging for a treatment they have designed after learning about drug therapy for depression and addiction, and my IB students recently used neuropsychology to fight off a (hypothetical!) zombie apocalypse. Day-to-day, I’m a fan of dual-coding to reduce cognitive load, and I like to support colleagues through resource sharing, being approachable and being consistent. Leading by example is important to me, and one way I do this is through modeling healthy work-life boundaries.

I’ve also become a recent fan of the thoughtful use of AI in the classroom, particularly for supporting differentiation and revision. Tools like Magic School have helped students gain feedback on their writing and check their understanding of theories and concepts with custom-designed bots. Used carefully, AI offers a valuable opportunity to personalize learning and engage curiosity.

I’ve also become a recent fan of the thoughtful use of AI in the classroom, particularly for supporting differentiation and revision. Tools like Magic School have helped students gain feedback on their writing and check their understanding of theories and concepts with custom-designed bots. Used carefully, AI offers a valuable opportunity to personalize learning and engage curiosity.

Looking ahead, I’m currently researching ways to incorporate animal-assisted education into my practice, something I believe could have a powerful impact on both staff and student well-being, engagement, and emotional regulation.

Beyond your professional work, you volunteer with an animal rescue charity. Can you tell us a bit about it?

I’ve always loved animals and have had pets since childhood. Being someone with sharp empathy, I’ve always found it difficult to see or hear about animals in distress and believe we have a moral duty as humans to help where help can be offered and is impactful. I started rescuing stray and hurt cats and dogs (and one snake!) in China pretty much as soon as I arrived, after finding a week-old kitten at the subway station. I bottle-fed her to health, and she is still with me now! I try to help out with Furry Tales animal rescue charity by going on rescue missions, vet visits, fostering, and taking part in charity events for fundraising when I can. It’s so rewarding being part of the process when an animal who has never known love finds their perfect adoptive home. The co-founders and those who volunteer at Furry Tales truly do fantastic and often thankless hard work. It’s almost another full-time job!

Let’s talk about education.

Having lived in China for more than a decade, what are some differences in education styles you’ve noticed here vs in the UK?

The biggest difference for me is the emphasis on being global citizens. At DCB, our mission is to Live Worldwise, and we teach our students to value diversity and develop the skills, knowledge, and motivation to make positive differences in the world. Working with international students certainly creates opportunities for rich cross-cultural dialogue in the classroom. Compared to the UK, there’s possibly more focus on developing intercultural competence. It’s nice to see students carving their role in shaping a more connected, passionate world alongside their academic pursuits.

The IB program emphasizes critical thinking and interdisciplinary learning. How do you tailor your teaching to foster these skills in psychology?

The IB program emphasizes critical thinking and interdisciplinary learning. How do you tailor your teaching to foster these skills in psychology?

Haha, it’s unavoidable in psychology! Critical thinking is at the very core of the subject. Sure, we learn theories and studies, but the real skill comes in being able to think critically about these, ask questions and transfer these skills across topics and, indeed, subjects. For example, when we learn about research methods, we don’t just learn the terms and definitions; we experience them through our own experiments and research, which we then scrutinize. There are many connections to other subjects, such as biology and global politics, so students start to see how psychological concepts are interwoven with broader human experience. This sort of critical thinking toolkit has advantages in an ever-changing world where disinformation is increasingly common – an important skill, I would say.

What are some common challenges students face in GCSE/IB psychology, and how do you help them overcome these hurdles?

What are some common challenges students face in GCSE/IB psychology, and how do you help them overcome these hurdles?

As psychology is often a completely new subject to GCSE students (and sometimes IB or A-level), the terminology can often be a little daunting. Words like “basal ganglia” or “Contagion heuristic” rarely appear in everyday vocabulary, and equally challenging are the wildly nondescript terms “Type 1 and Type 2 error,” which offer little in terms of language roots for students to try and decipher their meaning. To support, I integrate active vocabulary strategies right from the start. From dual-coding to low-stakes retrieval quizzes and student-led glossaries, the emphasis is on the use of the language, not just memorization, and this goes a long way in terms of psychological literacy.

Another challenge students often face in psychology is becoming friends with uncertainty. Unlike subjects that offer clear-cut and definitive answers, psychology lurks in the grey areas, where multiple explanations co-exist. For students who like neat conclusions, this can be daunting at first, but learning to tolerate ambiguity is the very essence of critical thinking. I always remind them that uncertainty is not a weakness; it is where real intellectual growth happens, and we joke that the answer to all psychology questions is “It’s complicated!”

How do you support students who struggle with the heavy content load or exam pressure of IB psychology?

The first step is to stay organized. Things move fast in the IB, and staying on top of things by reviewing lesson content each evening goes a long way in consolidating memory. I encourage students to build consistent habits in study routines early on, making use of psychological learning concepts such as retrieval practice and spaced repetition.

I also talk very openly about stress and pressure as these are very natural responses to challenging situations. Normalizing these feelings and giving students space to talk about them is powerful. I tend to focus on progress over perfection. Psychology can be pretty intense, but it is also very human, and I try to model that balance in my teaching.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on these…

We’d love to hear your thoughts on these…

What’s one thing you’d like parents in the international school community to know about how they can best support their high schoolers?

I’d say the most important thing is to believe in them. Progress can always be made, no matter the starting point. We should be encouraging students to show the best effort they can in their studies, but with that comes a responsibility to protect their well-being by ensuring there is always time for connection, fun and relaxation. When students feel supported at home, they are much more likely to take academic risks (a good thing!), bounce back from setbacks and stay motivated. It’s easy to get caught up in grades, but real long-term success comes from building habits of curiosity, resilience, and balance. So, if I could give one piece of advice, it would be to praise their effort and remind them that their worth goes far beyond only their academic grades.

How does your background in psychology influence how you mentor students dealing with stress or motivation issues? What are some tips you can give parents to better assist their child at home?

For parents, I think it’s important to validate your child’s feelings when they inevitable feel stressed or overwhelmed. It often can’t be “fixed” per se, but being listened to goes a long way. Also, structuring downtime is something that can help. Teenagers often think they know how and when to revise, but in reality, they are sometimes cramming until 3am the night before an assessment, which rarely helps them to achieve! Building a manageable study schedule together, with deliberate breaks and time for meals, regular sleep and social interaction, and, crucially, staying consistent with this, creates predictability, which in turn lowers anxiety.

If a parent wanted to encourage their child’s interest in psychology outside of school, what would you suggest?

Read! There are so many psychology-related books out there spanning a variety of topics, interests and reading levels. For teenagers, I often recommend authors such as Oliver Sacks, who wrote The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, or Steven Pinker for more generalized reading about the brain. There are many “Introduction to Psychology” texts available, including graphic novels. You can also explore online resources, including the British Psychological Association’s website, or podcasts such as Hidden Brain or All in the Mind. One thing to be mindful of is pop psychology – it can be entertaining, but it is not always scientifically grounded or accurate.

Psychology is everywhere! Even films like Inside Out, A Beautiful Mind, or Finding Dory can open up conversations about things such as mental health, identity, and cognition. Encourage your child to ask questions about why we behave in the ways that we do, perhaps in their friendships, in stories, in social media, or even in history. These conversations help us to connect what might become classroom learning to everyday life. Being curious is where a love of psychology truly begins.

Learn more about Dulwich College Beijing Senior School in their exclusive Taster Class:

Images: Dulwich College Beijing

Images: Dulwich College Beijing